A CICERONIAN LAWYER'S MUSINGS ON LAW, PHILOSOPHY, CURRENT AFFAIRS, LITERATURE, HISTORY AND LIVING LIFE SECUNDUM NATURAM

Sunday, December 24, 2017

The Birthday of the Sun

Not to contribute to or perpetuate the purported War on Christmas, but the early Church, or someone, was wise to co opt (or usurp?) this season of ancient celebration and designate it the Christmas season. But if it signifies the birth of anyone or anything, history tells us it is the birth of the Sun that is celebrated in the northern, or at least the northwest, hemisphere at this time of the year.

It's clear that this is time of the winter solstice. The Romans thought that it took place on what we call December 25, and that date was considered the birthday of Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun, the god of Aurelian and even of Constantine for a time. But long before them great significance was accorded that day when the Sun became stronger and stronger, and the daylight became longer and longer. Light was once again dominate over the Dark.

It's always been clear that we owe our own existence to the Sun, and that all life we know is dependent on it. Why not substitute the Sun, the giver of life, with the Son (of God)? Why not speak of the resurrection of the Son of God (and of other savior-gods) as we spoke and still speak of the resurrection of the Sun?

Even someone as pragmatic when it comes to religion as Napoleon said that if he was to worship a god, it would be the Sun, the giver of life, the ruler of the sky. It gives us food and warmth, it allows us to see what's before us. It's hardly surprising ancient people worshipped it, even to extreme lengths as did the ancient Mesoamerican civilizations. It would be surprising if they didn't.

And now we know that the Sun, being a star, is undoubtedly a creator; of the solar system, of us as we are the stuff of stars, true children of the universe and made of the same substances as all else within it. The Sun may not have said "Let there be light" but it made light and created our world more completely than the God of Genesis, and its part in that creation can be established with much greater certainty than the Genesis story.

So we're right to celebrate this time of year, and should do so, call it what we will. It is a rebirth of sorts, and a celebration of life, literally and figuratively. It's worthy of reverence if not worship by a Stoic, even; or perhaps even especially by a Stoic, who knows that the universe is divine and that we partake in it.

Sunday, December 10, 2017

The Quest for Ancestry

It seems that in these unnecessarily interesting and unnerving times, many of us have become fascinated with our ancestry. We investigate it not only in the old fashioned way--search of records--but are now able to do so by analysis of our DNA. DNA presumably provides a far less detailed picture of our lineage than would a careful record search, but this hasn't prevented the marketing and sale of DNA kits. People, or some people, long to know what groups of people have combined to produce them if not their individual ancestors themselves.

Why have many of us become inclined to investigate our ancestry? The ancient Romans, or at least the patricians among them, valued their ancestors considerably. Portrait masks of ancestors were made and displayed by them. Actors would don those masks and famous ancestors would thereby make an appearance at important occasions like a triumph or games given in honor of a particular member of a great family. None of these masks have survived, but we know of them from sculptures like the one appearing above. The devotion of the Chinese to their ancestors is well known. Ancestors were also important, and may still be, to some of noble descent, to kings and queens that remain.

This is a concern which hasn't been of much concern to most of us, however; not at least to the extent that it seems to be now. But we have resources available to us now our ancestors didn't have. Has this made a difference in our desire to investigate from whence we came?

Perhaps it has, but there may also be other factors at work. We live rootless lives in a rootless time, I think, and seek roots as a result.

I say "rootless times" because it strikes me that what has rooted us in the past here in our Glorious Republic and perhaps the West in general no longer does so. Traditional religion is uninspiring to many. Liberal democratic values provide little support or comfort. How could they, now, when it seems our democratic system, which was never all that democratic to begin with, is apparently failing? We have gone from electing such as Washington, Adams and Jefferson to electing an ignorant and often incoherent buffoon, and have matched him with a venal, oafish crew of legislators lacking the intelligence needed to legislate and utterly without principles.

"Rootless lives" seems apt as we seem to lack the steadiness required to think intelligently ourselves. Instead, we grasp at anything or anyone providing a simple answer to questions we face which in turn demands only the most thoughtless response to any problem. In a sense, ignorance of anything new or different is indeed bliss, though, perversely, it is what we are quick to accept unthinkingly which demands new and different answers.

There's a certain comfort in being able to say my ancestors were so and so or such and such. An association is created which we can use to provide ourselves with an identity, a character, ancestral customs, ancestral values, which already existed and perhaps have existed a very long time. We have them ready-made, as it were; there's no need to manufacture them ourselves.

And it may be that we look to the past as it's unusually difficult, or maybe even disturbing, to look to the future. There are times when many will have few expectations, and rightly so. This, it seems, is one of those times for most of us. There may be a "happy few" but their happiness becomes more and more extraordinary.

The past can be an escape, as many historians and fans of history have found.

Perhaps we seek hope in our pasts as we can have little hope in our futures. That's a troubling consideration, but it's likely that as it is such, few will take note of it.

Sunday, November 26, 2017

Selfishess, Salvation and the Supernatural

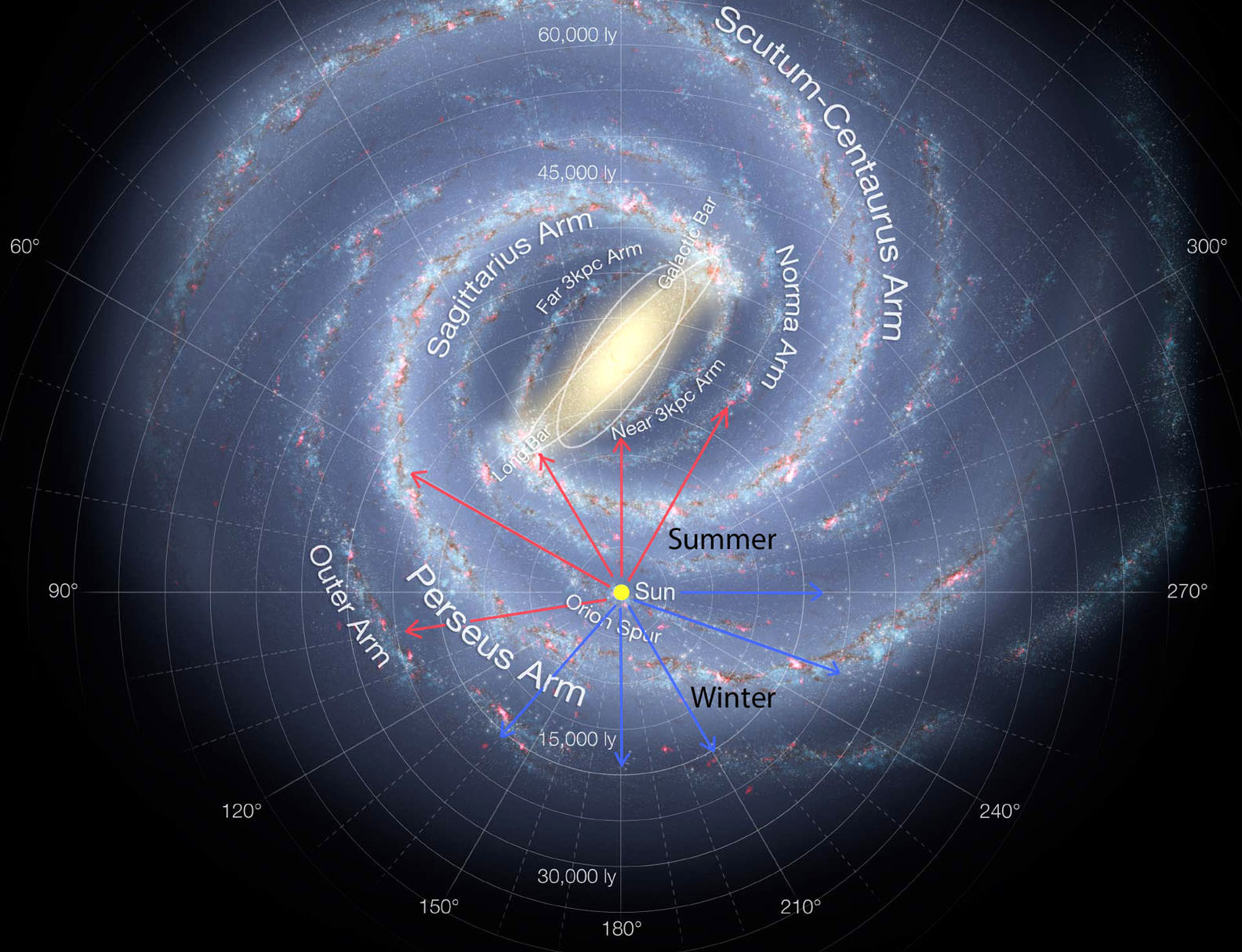

The Milky Way, the galaxy of which our world is but a tiny part, is itself only a tiny part of the unimaginably vast universe in which we and all we know exist. Why do some of us insist there is "more"?

There is certainly more than we know, of course. We know only a very little of the universe. What I wonder, though, is why some of us believe there is more than the universe--by which I mean more than nature, i.e. the supernatural.

That very odd man, Cardinal Newman, in his Apologia, I think, wrote that he felt from an early age that the real world we know isn't "really real" but that there was something else lurking behind it, as it were. I find this view as odd as the man himself, even odder. What we insist on calling "supernatural" seems to me to be very much like what we know in nature made or perceived as strange. Ghosts, for example, are eerie figures which were people and so resemble people or are people but in an unusual form. The transcendent God many believe is, apparently, the perfect form or creator of all that we creatures of nature find admirable; but what we find admirable we admire because we know or believe it to be so naturally--we encounter or experience it within nature.

It strikes me that what we believe to be supernatural is more easily conceived of as being part of nature, of the universe that is, but part of it that we don't yet know or understand. People ignorant of quantum physics too often refer to it as somehow establishing something or other. I'm certainly ignorant of it myself, but what little I read and comprehend of it seems bewildering enough to indicate that we have much more to learn about the universe. With so much more to learn, why do we purport to envision anything beyond it? How can we even guess what that might be?

I would guess that belief in the supernatural results from a dissatisfaction with the natural. That dissatisfaction can only be one arising from a very narrow point of view of nature. This is necessarily the case because it must arise from the perspective of a dissatisfied person.

There's certainly enough to be dissatisfied with, of course. It's likely that's always been the case, and likely as well that there was even more to be dissatisfied about in the past. But the fact remains that nature dissatisfies because our perspective of it is ultimately a selfish and, relatively speaking, small one. The supernatural being unnatural or a-natural doesn't disappoint or rather can't disappoint because it isn't real and may be anything we want it to be.

Dissatisfaction with the world is necessarily selfish, and so it isn't surprising that satisfaction with the supernatural--that which isn't part of the world and so cannot be attained until we're not part of the world--is selfish as well. In other words, the afterworld or otherworld where we go when we're out of nature is hoped to be what we would be satisfied with, unlike the world in which we now live. We're thought to attain this desirable afterworld if we're worthy; if we're saved. The reward for salvation is in that sense intensely selfish as well. We are saved. Others may be if they are saved; or they may not be.

So it seems to me, in any case, as part of this speculation or train of thought.

This emphasis on the supernatural, on the transcendent, is therefore an exceedingly personal one. Which to me raises the question whether it is truly moral.

Concern for the welfare of others is a concern which is properly directed towards living in nature. Concern for their "immortal souls" is a concern with the supernatural. Perhaps that's why we've always been less concerned with the lives of others than we purport to be or than we say we should be.

It isn't surprising that those who refuse to cherish nature believing it to be secondary and who maintain that we're apart from nature rather than a part of it should be supremely selfish, because the world and all that is in it is essentially not their concern. It cannot be, not "really." We suffer from a disregard of the universe though we barely comprehend it. Our belief in transcendence dooms us to disconnection with the world and others.

Friday, November 17, 2017

Of Cupidity and Stupidity

The quote above is from one of Shakespeare's lesser-known (to me, at least) plays, Troilus and Cressida, and is brought to mind by...what should it be called? A tsunami, an avalanche? In any case, the continuous claims of sexual harassment being made on what seems a daily basis here in our Great Republic against quite a few people, that is to say, against various men, by both men and women.

It seems rather remarkable even to me; a lawyer and therefore someone accustomed to and perhaps even dependent on wrongdoing of one kind or another (by others, of course). But even those of us who thrive on the misdeeds of humanity must admit to surprise at what seems to be a unique moment in tawdry history.

The law of sexual harassment has been around for quite some time, in the U.S. at least. It's something I've known of professionally and have had cause in my practice to become to be acquainted with, now and then, over the past several decades. One would think that employers and employees, in particular, would be aware of it and fear its application given the litigation and claims through state and federal administrative agencies which have taken place and the stern warnings lawyers and human resources types have issued for many years now.

So in one sense I find it puzzling that sexual misconduct of this kind is so apparently widespread. How can anyone be so blithely unconcerned by it? How can so many men indulge in it, that is to say, without fear of the consequences?

I also find it puzzling that there are those who feel that sexual harassment is, at least in some cases, something which shouldn't be of great concern, or can be excused as "boys being boys" or harmless play. The law is the law. It doesn't matter whether one agrees or disagrees with it, or whether it's thought of as too much or too little. It's foolish to be anything but prudent and so to respect it even if one doesn't respect those it's intended to protect.

But fools we tend to be, particularly where sex is concerned. I think that any more than casual observer of human conduct must acknowledge that lust, lechery, sexual desire--whatever it should be called--can render us extremely stupid. I think that particularly in the case of men it makes great, gaping idiots of us all unless we take steps to control our own desire. And, it's such a completely selfish, narrow and powerful desire or impulse that the consequences to ourselves and others are disregarded.

This isn't to justify sexual harassment let alone explain it, but to recognize that the urge behind it is there almost always and must be restrained. If it isn't, we do stupid, harmful, cruel, immoral things and should pay for it in one way or another.

Add to this the understandable concern victims have that making claims of sexual harassment will subject them to shame and ridicule and even have financial consequences if the perpetrator is powerful and influential, and it isn't so surprising that it goes unchecked in too many cases. It seems that could be changing, though.

Unfortunately, as Shakespeare or his character noted, lechery like war is always in fashion among us, and tolerated by us. It must remain to be seen whether sexual harassment will diminish as a result of the rising intolerance towards it or whether our remarkable lack of sense and control in this area will continue. I think it's a good sign that even those who have previously been given a pass, most ignominiously, in this area (yes, that former president for example) are being recognized and condemned as predators.

Given those accused, though, I wonder if older men are particularly prone to this behavior. Do older men act in this fashion because they know their failing looks and powers make it less and less likely anyone will want to have sex with them? It's been well said that there's no fool like an old fool.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Sancta Mater Ecclesia

Holy Mother Church, or Sancta Mater Ecclesia in Latin. The One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, just as it's said, also in Latin, in the interesting picture above. Or, according to the inscription at the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, built at the order of the Emperor Constantine and dedicated in 324 C.E. by Pope Sylvester I, omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput, the mother and head of all the churches in the city and the world.

Old Mother Church, in truth. Quite old, really, as age is measured in human history. As I've posted before, I have a sentimental fondness for it as it was at one time, during my youth. It gave a certain joy to my youth, as we as altar boys said its God did as we went to God's altar, or if not joy a kind of distinction.

It's curious how we refer to institutions, particularly those we look back upon in fondness, as "mother." We call our old schools Alma Mater. I suppose we can call Mother Church the same, as it can be said to have nourished us Catholics for a time. But nourished us in what exactly?

It must be admitted that one thing Mother Church encouraged, probably throughout its long history, is reason, or more particularly reasoning, as it was developed before the Church came to exist. That may seem an odd thing to say, given that the beliefs of Catholicism, taken literally, seem unreasonable. That's likely why they often are not taken literally, particularly by those believers who reason or employ reason in its defense.

Regardless, though, I think it fair to say that the Church has always honored reason and reasoning. The Church Fathers employed reasoning in condemning the pagans. Tertullian, a lawyer, knew reasoning in the form of rhetoric at least. That was a lawyer's tool, particularly in those times. The Church Fathers, like Augustine, knew their philosophy (pagan, of course) well, and were educated in the manner in which ancient pagans were educated and had been for centuries. The great pagan philosophers didn't take pagan religion literally, either. Why should Christian philosophers?

So, I think the early Church soon abandoned the position seemingly taken by Paul, rejecting the "wisdom of the wise." Instead, it accepted it; assimilated it, in fact, and made it serve the purposes of the Church.

I think its also fair to say that the Church has always honored culture, education, history. It kept the wisdom of the ancients alive, through the work of its monks, even if they functioned as mere scriveners, patiently copying the great works of the past. As a result it fostered great thinkers even during what are called the Dark Ages; Abelard, Duns Scotus, Aquinas, Bonaventure, William of Ockham; it's an impressive list. It borrowed from the heathen as needed in order to do so, and so rediscovered Aristotle via learned Moslems. Aristotle so impressed churchmen he was called "The Philosopher." Thomas Aquinas famously modified Aristotelian thought so as to make it the foundation of Catholic philosophy--known as Thomism. It still has its adherents today.

For these services Mother Church deserves honor. I wonder, though, if in inculcating its sons and daughters with a love or reasoning, culture, history and education Old Mother Church gave her children the learning needed to lead them to think her cupboard of reason was, ultimately, bare, as that of Old Mother Hubbard was bare of nourishment.

Learning can be dangerous to a religion, especially when learning involves fostering the capacity to reason, to think logically, to ask questions. Eventually, those questions address the fundamental premises of Catholicism and Christianity, e.g. the divinity of Jesus, Original Sin, Heaven and Hell, the Trinity, the redeeming character of the sacraments, transubstantiation. What could be their justification? How can they be justified, in modern times? How could Jesus be both God and man? What sense does the seemingly endless list of sins, so specific to human beings, and a belief in a God-man, make given the vastness of the universe and given that our world is such a tiny, tiny part of it?

To someone trained to reason, recourse to revelation and faith is unpersuasive. It's a kind of resignation.

Mother Church certainly has managed to survive for centuries, so perhaps it hasn't arranged its own destruction after all. Perhaps it hasn't undermined the fundamental beliefs which make it distinctive. But it seems to me that it does, necessarily. And so a choice must be made, to be Catholic by disregarding reason or accepting that fundamental beliefs or premises are not to be "taken literally." But that, it seems to me, is to accept a Catholicism, a Christianity, which has lost all which makes it distinctive.

Monday, October 30, 2017

Some Thoughts on Modern Paganism

The word "pagan" is derived from the Latin paganus, which was used to refer to someone from the countryside, someone rustic, unsophisticated, unlearned; something of a bumpkin, I suppose. As Christianity came to take hold in the Roman Empire, it began to be used, by Christians, as a term of disapproval or contempt, referring to those who were not Christians. This may make a certain kind of sense, as those who recognized the old gods came to avoid urban areas which Christians came to control or where Christian intolerance was prevalent (except, perhaps, Rome itself, where the aristocratic old families remained stubbornly attached to the older religion). The old beliefs and rituals survived in the countryside, it's said, for centuries after the advent of Christianity. They may survive even now, in modified, Christianized form.

Halloween may be considered a particularly pagan time of year. By Christians, that is. I'm not sure, myself, just how pagan it may be. I suppose Christians think it pagan because they associate it with Satan and his minions, and Christians have long thought pagan gods to be demons of one sort or another. But Satan himself isn't much of a figure in traditional paganism. There is no Satan among the Greco-Roman pantheon, for example; no Satanic figure at all, really, except physically in the form of Pan. Pan, though, is otherwise not very Satan-like. The Devil seems to be a peculiar fixture of the Abrahamic religions.

What's referred to as Modern Paganism, or Neo-Paganism, seems to be groups of people who for various reasons practice what they think to be ancient pagan rituals and hold what they think to be ancient pagan beliefs. It's claimed that it's growing. Some modern pagans are adherents of Wicca, a kind of witchcraft revival hatched in the mind of a retired British civil servant in 1954. Some follow the Norse gods, or certain of them. Some think of themselves as Druids. Some are followers of a goddess or the goddess, and are convinced that such worship is in effect the original religion, when society was, it's claimed, matriarchal long before the advent of the sky gods.

Some hold various beliefs which involve nature-worship, theistic, polytheistic or pantheistic. Some may be considered Deists. Modern Paganism has been around for some time, I believe, and is in some respects a phenomenon of the late 19th-early 20th century when many became interested in occultism or spiritualism, or became enthralled with ancient Egyptian religion after the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen, when Madame Blavatsky and others sought to resurrect Hermeticism or something else which could be said to have a pagan pedigree.

It would seem that Christianity, though otherwise remarkably successful in quashing paganism for centuries, hasn't managed to destroy it utterly. Nor has its efforts to assimilate it been entirely successful. It retains its magic. This shouldn't be unexpected, as it existed and flourished for thousands of years.

I doubt, though, that the pagans of our times live, or think, or believe as did the pagans of the ancient past. It simply isn't likely that they could after all that's happened. The picture at the beginning of this post is of a relief showing Marcus Aurelius making sacrifice. Animal sacrifice was essential in Greco-Roman paganism, performed in complicated rituals. Livers of animals were perused by haruspices in ancient Rome, a form of divination the Romans learned from the Etruscans. Who today could honestly ascribe to such ceremonies the significance they were accorded by the ancients? Who, indeed, could perform them?

Who knows what the Druids did, really, or what they believed? Our sources of information about them are Roman and so unlikely to be sympathetic or entirely accurate. How many moderns believe, sincerely, in witchcraft? How many while joining hands and chanting at Stonehenge or some other ancient site can really claim to be believers of the kind who did the same, if indeed they did the same, so long ago? None of them knew or had experienced what we know and experience now. Given that knowledge and experience, would they believe now as they did then? How could they?

There's no reason (unless we accept the view that they were deceived by demons) to think ancient pagans were not sincerely pious, and it must be assumed the beliefs of many of them were fervent. But that piety can no longer be shared, or even imagined.

I suspect there's a great deal of Romanticism involved in the efforts to recreate paganism, as well as what may be a longing which cannot be satisfied now by Christianity as an institutional religion. But we fool ourselves if we believe we can be what pagans were. They were different from us in matters of faith, in mystic belief, in ways too profound for them to live again in us, or for their beliefs to be shared by those living now.

Monday, October 16, 2017

Unfree Women, Unfree Men

The cartoon above is one of a series drawn by James Thurber, entitled The War Between Men and Women. The title of this post is a modification of the title of a collection of the works of Camille Paglia, Free Women, Free Men, which I'm now listening to her read to me in the relative comfort of my car as I go about my travels. Yes, there's almost certain to be a subtitle to the book of some kind, as seems to be the fashion, but if there is I can't remember it as I type.

I have a fondness for the incendiary Professor Paglia. She's libertarian, which I still think of as my own position when it comes to the imposition of government power regarding what people think, say and do (within reason--I'm an aspiring Stoic, after all). She seems to have a comforting respect for science, which is remarkable in an academic, as well as freedom of speech, and is opposed to what appears to be the attack being made on it in the hallowed halls of the Academy, and the oddly repressive and totalitarian views which are being thundered by its denizens at society in general and at the young in particular whom we hope to educate. And she's of Italian descent, as am I, being a direct descendant of the great Marcus Tullius Cicero. Well, not really, but I am clearly a Ciceronian and am of Italian descent.

I tend to agree with her as well that sex isn't entirely a social construction, and that there are certain biological differences between the sexes that cannot simply be disregarded, and may be disregarded only at our peril. I tend also to agree with her that there are feminists whose hatred of men has overwhelmed their ability to reason, and who see male and female in perpetual conflict until the male disappears. Where I disagree with her is in the emphasis to be given sex as a cause of or motivation for everything, or anything. It strikes me that she feels it to be the basis for all we do or have done.

It's odd, to me, that although she gives sex, as biology, such emphasis, she also contends that all we do or have done of any significance is the result of our desire to escape nature's hold on us. This is particularly true with respect to what men have done in creating society, technology, law. Men, if I understand her correctly, strive constantly to escape the overwhelming, suffocating dominance of their mothers, and their achievements are the result of this striving. Art, in particular, is humanity's effort to detach itself from nature, according to Paglia.

No doubt I'm putting her position poorly. Regardless, though, I find it odd that although she refers to our opposition to nature and efforts to conquer or subdue it, and lauds it, she clearly feels we're subject to our natures, specifically our biological natures. We are therefore, I would say, parts of nature. We're not in battle with nature or in opposition to it because we're not in opposition to ourselves. I think she makes the hard distinction between humanity and nature that's plagued Western thought since at least the time of Plato. In order to make that distinction, I think she must accept the mind-body distinction as well. Our minds are in conflict with nature, though our bodies are parts of nature, and our minds thus are in conflict with our bodies as well.

If we think of ourselves as part of nature, living creatures existing in an environment and interacting with it and other creatures, this sense of dire opposition disappears. We do instead what every other creature does, attempt to satisfy our desires and resolve or avoid dangers. We happen to have an intelligence which permits us to interact with other parts of the environment in a more satisfying and successful way than others (as far as our wants and needs are concerned), but that doesn't mean we're at war with the rest of nature. It's uncertain whether we can even claim to be unique in our use of language or in the production of art, given discoveries being made in the conduct of other animals.

As for the prevalence of sex, sex as the primary if not the sole cause of all we do or think, there's no question that it fascinates and obsesses us. But that, and the tendency to ascribe to it such causal significance, may itself be a social construction. It's importance is obvious. Not so obvious, to me at least, are the reasons that it is accorded even greater importance, why it is considered, in effect, all-important. Why does it figure so completely in our art, law and religion? Can this be said to arise solely due to biology, to our hormones, to our physical nature? Or, might it be the result of efforts made to glorify what can in fact be considered a "simple" biological need present in all creatures, to make of it by custom or otherwise something much more of a social and cultural feature than it need be for reasons that are not simply the result of our biology?

Also, and obviously, if we are in fact so driven by sex, it's questionable to what extent we can be referred to as "free" and if we can be so described, the question arises: Just how free are we, if what we do is so influenced by sex? What I suspect Paglia means to say when she speaks of free women and men, is that we should be free, just as she says we should be equal, under the law.

I'm suspicious of theories regarding human conduct, society and culture that posit a single cause for all, that envision a kind of First Mover behind what we do, to which all may be traced. Suspicious, too, of categories, like Apollonian or Dionysian. They may be useful generalizations, but are clumsy explanatory devices when applied to all we do and are. Our aims should be more modest. Totalitarianism begins with the belief that there is a single, simple answer or truth that has been found, and must be accepted by all. That's a belief system which isn't eradicated when another single, simple answer or truth has been found, which must be accepted.

Labels:

Art,

Camille Paglia,

Culture,

James Thurber,

Law,

Sex,

Society

Monday, October 9, 2017

The Return of Zardoz (Guns Galore)

I last addressed the totemic status of guns in our Glorious Republic a few years ago. Another massacre, another gun control "debate" (such as it is). It's time for the floating head of Zardoz to appear once more and thunder its message, so dear to so many, that the gun is good. As for the penis, it's self-evidently evil here in God's favorite country, but also self-evidently indulged regardless, particularly by those who claim most loudly that it's evil. Much, I suppose, could be made of our quasi-religious belief in the sanctity of guns and our fascination with sex--our repressive horror of it and nervous exultation in it. But it's a tiresome train of thought I won't board.

But our strange, compulsive regard for guns is interesting in itself, as it admits of no limits. There are those who feel that we have the right to own (and carry) as many as we like, of whatever kind we like. Nobody seems to be struck by the oddness of the fact that the most recent killer had so very many guns, and even explosives. The concern expressed is how he accumulated them without triggering some kind of warning. But what kind of person would want to have so many? He wasn't a collector, clearly. Is it plausible to claim that he felt they were required for self-defense? Only if he was an exceedingly fearful man, surely. Also, it seems clear enough that defense wasn't his concern. Is an interpretation of the Second Amendment which countenances having so many guns a reasonable one?

Where does the right to arms end, or does it end? Do we have the legal right to arms of any kind? Artillery? Surface to air or surface to surface missiles? Tanks?

Reductio ad absurdum sometimes is considered an inappropriate argument, but seems to me entirely appropriate when confronted with a belief in an absolute, unrestricted right. One might say that there are particular arms which most cannot afford to have or maintain or possess, but still have the right to have under the Constitution. What one claims to have the right to under the Second Amendment impacts the reasonableness on one's interpretation of it.

One need only admit that there are limitations on rights provided by the Constitution to admit that such rights are appropriate when they're reasonable. As Constitutional rights are subject to limitation and have been throughout our history, there is no reason to contend that the right to possess arms is without limitation. What constitutes reasonable limitations then becomes a topic of debate. This seems to be a debate the more avid proponents of the Second Amendment would rather avoid.

The reason for this may well be that there is no reasonable way to support the claim that people should have the right to own as many arms as they want, own automatic or semi-automatic weapons, own devices which allow them to use weapons as if they were automatic, carry about weapons with them whenever they wish, etc. Beyond the more fantastic claims made by those who think the government is out to get them, or who think they must protect themselves from harm in a restaurant or store, there is little on which they can rely. Fear doesn't go well with reason, and instead dispenses with it. Fear seeks absolutes. Fear relies on absolutes.

Monday, October 2, 2017

The War I Missed

I turned 18 in 1972. That was the year the last draft lottery took place. The lottery applied only to those who had been born in 1953, though, and I was born in 1954. I duly registered for the draft, but consequently wasn't drafted. My draft card lies somewhere among the debris I've accumulated over the years, but there is no other token of the Vietnam War among that debris, nor did I become debris of that war as many others did. The Burns/Novick production The Vietnam War serves to remind me of the war I was fortunate enough to miss.

I didn't know when I registered that there was no chance I would be drafted, unless another lottery was held. In fact, I knew little enough of the war itself. Though a Boomer, I wasn't an old enough Boomer for the war to have a great deal of impact on me personally. I knew no veterans at the time. As far as I can recall, there wasn't much discussion of the war among my friends in high school, or even in college. We weren't threatened by it, not really. By the time I graduated from college, of course, the war had ended.

What I remember of the war and those times is what I saw on TV or read in the newspapers. Like most whose exposure to the war was thus limited, I knew very little, relatively speaking. I never participated in a protest march. I never protested. I was 14 at the time the 1968 Democratic convention took place in Chicago, and saw footage of the rioting, heard the speeches at the convention, or some of them, watched the now famous, or infamous, Buckley/Vidal debates with what comprehension I had as a 14 year old, which I think wasn't much.

I'm a fairly avid reader, though, and read of the war as I grew older. I knew, for example, that in purely tactical terms the Tet offensive was a miserable failure for the North long before the work of Mr. Burns and Ms. Novick appeared on our TV sets, and knew also that our nation wasn't particularly impressed by that fact. I knew the argument that we should have won, but could not win as the war wasn't supported by the nation. I knew that this lack of support was sometimes blamed on liberals or the liberal media. I tend to think that an empire failed to do justice to its soldiers, and failed even to recognize that it was an empire engaged in a war of empire, between empires.

I knew the argument we should not have been there in the first place, knew of the incursions into Laos. the troop withdrawals late in the war, the largely ineffective "peace talks", Kent State, the march on the Pentagon (I read Norman Mailer's The Armies of the Night; also Miami and the Siege of Chicago), the murders of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the campus protests. Much is called to mind in watching Burns/Novick's version of the war.

What I didn't know, most of all, was what happened to those who fought or otherwise served in the war. This documentary does us a great service by informing us of what happened to them, and what they thought and think about it.

I think that if I had been drafted, I would have been one of them in some capacity or another. I had no objections to the war which would have sufficed to prompt me to seek refuge in Canada, and didn't think of myself as a conscientious objector. What I find most remarkable, and disturbing, is how little touched I was by a war that took the lives of many of those but a year or two older than I was; it's an unsettling fact. Perhaps our sense of history is ultimately selfish, or perhaps mine is, in any case.

Very few of those appearing in the documentary come out looking well, outside of those who fought. For them I find it impossible to feel anything but pity and respect. Those objecting to the war appear small. It's possible, of course, that objections to the war could have resulted from the belief that the war was immoral, but the protesters preening in front of the cameras hardly seem heroic or lit with the fire of righteousness. Pity for them is appropriate when they're killed, as were those at Kent State, or beaten, or jailed if for merely expressing an opinion. How many of them were, though? The politicians seem even smaller, in fact despicable.

In the end, America did what was politically expedient. Arguably, that's what it did when it became engaged in Vietnam in the first place. Arguably, that's what it does now and what it will always do; what is all it can do.

Monday, September 18, 2017

"Let Be Be Finale of Seem"

The sunset is a kind of finale, though not one as final as death. It's the finale of a day, which may indeed be remorseful as A.E. Housman wrote but need not be. Remorse is understandable at the end of a day, or a life, to one who is thinking at the end of one or the other, because it's not uncommon to feel remorse for what was done or was not done which could have or should have been done. Humans being what they are chances are excellent that they should have or could have done something and that something they did was wrong.

What seems to be isn't necessarily what is. To be is to exist. What exists may seem not to exist. You get the picture (or at least you get what the picture seems to be).

"Let be be finale of seem." Let the end of our efforts to determine what seems to be, be? Let what seems to be, to us, be? Or, let it be, in the sense of give it up, forget about it? Give it up, this tendency we have to distinguish appearance from reality, to insist on a thing-in-itself that we cannot know? Give up the belief that what seems to be reality isn't really reality (the really real)?

I'm impatient with metaphysical and ontological concerns, i.e. the issue of Being and, that other favorite, Nothingness. That may be a failing on my part. I'm unconcerned with questions regarding what it is, in all cases, to be or not to be (was Shakespeare having a bit of fun with philosophers when he wrote this speech of Hamlet? I find myself hoping so). The fact that we make mistakes sometimes leaves me unimpressed. It hardly seems grounds on which to question all we interact with naturally, by living, with considerable success, much less envision some kind of place apart from the world on which all truth and beauty depends.

So, I would interpret Stevens as saying that what is, is in the end what seems to us to be. In the end of the day, in the end of us, you and me. Let it be so.

"Things Merely Are" is the title of a book by Simon Critchley about philosophy in the poems of Wallace Stevens. It seems a less than hopeful phrase, but it's an assertion that renders a good deal of speculative philosophy superfluous. And, if that was what Stevens was attempting to say, in his poetry, it's something few other poets have said, I think. Yet there's unquestionably beauty in his poetry, just as there is unquestionably beauty in things of all kinds.

Consider sunset, especially as pictured above. The sunset merely is, of course, but though we don't cause the Earth to revolve or the sun to exist it is what it seems to be to us, the end of a day, and though it can seem to be, to us, a splendid end or a dismal, dull one, it's nonetheless an end of something.

We're edging into Autumn, now, and in that part of our Great Republic in which I live the leaves will turn glorious and then wither and fall. Crops will be harvested, vegetation of all kinds will stop growing, weather will turn cold. As we've known since ancient times, we wither and die like other things in the world do. But some of the most striking sunsets I've ever see have been winter sunsets, when the world seems, and is, dead. Those sunsets merely are as our deaths merely are.

Monday, September 11, 2017

The Ambivalence of Henry Adams

I've tried for some years now to read The Education of Henry Adams. I have not succeeded in doing so. I'm trying to read it once more, and this time have read more of it than I ever have. I'm uncertain whether I'll be successful in reading it all.

This disturbs me, as it's a work which seems to be admired by almost everyone. Gore Vidal, whom I admire as a writer (but not necessarily as a public figure) was very fond of it indeed, and wrote that there was something of a competition on the death of a relative or friend regarding who would receive the deceased's copy of the book.

It's a curious book, often described as an autobiography but if so not one which even pretends to set forth events which took place in a more or less objective manner (to the extent that's possible). It's instead a commentary regarding certain aspects of Adams' life and certain people he encountered while living it. It is well written, but as a commentary, not as an effort to relate what took place. Adams is uninterested in describing what took place. He wants instead to tell us something of what he thought of what took place while it took place, but most of all to tell us what he thinks now about what took place and those who were there while it took place including, perhaps most of all, himself.

There's nothing wrong with the author of an autobiography being interested primarily in himself, of course. A certain level of self-interest and self-regard is required if an autobiography is to be written. Nor is there anything necessarily wrong with an autobiographer using the opportunity provided to opine regarding people and things in his or her past.

What I find somewhat peculiar, though, is that Adams does nothing but opine about them. It seems the entire purpose of the book. What I also find striking is that Adams never seems to wholeheartedly admire, or write well of, anyone or anything. That includes his famous grandfather and great-grandfather, and his own father. Whenever he describes a talent or ability of a person, he invariably notes, as if to offset it, something lacking in him. The same goes for any institution. It has certain good qualities which he will mention, but is otherwise deficient in some sense. The deficiencies of any person or institution, inevitably, are greater than the merits; or it seems at least that he spends more time remarking on their inadequacies than he does on their good qualities.

For example, he attended Harvard College which was good in its own way, inoffensively and efficiently preparing its students for life in the world, but provided a poor education. His classmates included such as O.W. Holmes and the son of Robert E. Lee, but Holmes at the time was nothing to write home about and Lee, though sociable and having leadership qualities was an angry, stupid, thin-skinned drunk liable to leap at you with a knife if he thought you had offended him. Adams' father, Charles Francis Adams, was amiable and remarkably even tempered, but dull and something of a dunce.

Life seems to have been a series of disappointments for Henry Adams, overall. The world and all that's in it was on the whole somewhat dispiriting. It in any case contained nothing, apparently, which Adams thinks was wholly good. What was good wasn't quite good enough, and was in some way bad. Nothing seemed worthy of any great effort on his part.

This perhaps is why he didn't go into public service as his ancestors on the Adams side did. His grandfather and great-grandfather were presidents and his great grandfather was a Founding Father of his country, a revolutionary. His father served as U.S. Ambassador of England. He accompanied his father as a clerk, it's true, but his natural tendency seemed to have been to comment on people and things, not very approvingly, as an occasional journalist and historian. He didn't soldier in the Civil War.

He may have been one of the first public, or even professional, full time intellectuals. He had a kind of salon, at which he and others of like mind met and discussed significant matters. He seems to have been especially fond of clever young women, his "nieces" as they were called. He had an ongoing, though it seems platonic, relation with the beautiful daughter of William Tecumseh Sherman. His wife committed suicide, and he took the trouble to destroy all her correspondence and indeed never wrote of her, even in his "autobiography", and it seems didn't speak of her after her death. This led some to speculate that he had been unfaithful to her.

A peculiar man, then, and one given to judge others, not too kindly. He was apparently also a notorious and savage anti-Semite. His friend John Hay commented that he would have attributed the eruption of Vesuvius to the Jews.

It's possible his propensity to see and speak of the deficiencies in all people he knew or encountered, and any human institution he experienced, may have been the result of having a judicious mind. But one has to wonder, reading this book, whether he was ever enthusiastic about someone or something, or whether he found fault wherever he looked, for all his life.

Intellectuals, it seems, live to criticize, and are never really content in doing anything else. Henry Adams may have been representative of the decay of a great New England family (he never was particularly fond of Boston, either). Or he may have been simply more astute than anyone else. He may have relished and thrived in his disappointment and ambivalence; it may be that he wouldn't have enjoyed being content or happy, at least if it meant that he would not be inclined or able to find fault with someone, anyone.

The education of Henry Adams was apparently an education in the faults of others, and even his own faults. These faults weren't formally taught, and so were not part of his education or that of anybody else, but simply were made evident to him as part of our existence, which he observed and wrote of, disapprovingly for the most part.

Monday, September 4, 2017

The Dead Languages Society

It seems there is a difference between "dead languages" and "extinct languages." An extinct language is one that is no longer spoken. A dead language is one that is no longer the native language of any living community. Latin is an example of a dead language. It is not the native tongue of any person now alive. However, it "lives" in the sense that it is still spoken by some, read by some; some even write it. So, the Latin phrase shown above, which may be translated as "Long live dead languages," isn't nonsense. It actually makes sense, to those who study Latin and other dead languages and delight in creating such phrases. Better yet, I think, is Sola Lingua Bona est Lingua Mortua, which is to say "The only good language is a dead language."

In the Western tradition, Etruscan is a good example of an extinct language. Nobody speaks it; very few can read what examples of it we have, and then can only do so in a very limited way. It hasn't been figured out yet.

It's interesting to view the lists of dead or extinct languages which can be found in such sources as Wikipedia. What is striking about these lists is that the languages shown as dead or extinct significantly outnumber those which are "living." Dead or extinct languages may have been transformed over time and become living languages, as Latin became Italian, Spanish and French. Or they may have been annihilated in the course of cultural assimilation. The English and Americans insisted that the children of those they conquered learn English. They even thought they were doing them a favor by conspiring in the destruction of native languages. And of course they were not alone in this linguistic imperialism.

The extinction of a language is, I think, a real tragedy. So essential is language that it may be said not merely a people or a culture but an entire world is lost when this takes place, or at least a world view, i.e. how the world is perceived by a people, how they interact with it. It's a kind of genocide. The extinction of languages is something like the extinction of those who spoke it. If that's the case, then our history has been a series of extinction events; hundreds of cultures have been lost or destroyed, ways of living have been wiped off the planet.

English is neither dead nor extinct, of course, but it's interesting to speculate regarding whether it will be one or the other, in time. I think it's more likely it will be transformed. It may be that American English will be transformed through the slow progression in the use of Spanish in the U.S., which will take place regardless of the efforts of those who will, whether they like it or not, die soon enough and likely not be replaced or replaced by a steadily dwindling number of their descendants with the same reactionary views. Or, and this is especially interesting, it may be that English will be transformed by the technology which now encourages us to use it less and less.

It happens that technology at one time contributed to the use of language in the sense that it led to the growth of written language. Increasing sophistication in the use of tools to increase agriculture and the production of goods resulted in an increase in communities and transactions between them and individuals, which in turn fostered the development of means of written communication to express law and memorialize commercial transactions and eventually treaties, the use of numbers and signs to represent them, etc. Or so it's traditionally thought.

Now technology promotes the devolution of written language. Thus we're developing a kind of shorthand, a restricted form of English employing letters as words by virtue of the way they sound ("you" becomes "u"), the use of abbreviations which have become instantly recognizable (e.g. "lol"), and emojis. The day will come, I predict (for all I know it may be here) when poetry, prose, lyrics are crafted on the basis of such devices of language; we may develop a new kind of hieroglyphic language.

Old English died out long ago. What will be come of the English of today? The chances of it being superseded as it superseded other languages are slim, I believe, but its users and their technology could well render it radically different from what it is now.

In the Western tradition, Etruscan is a good example of an extinct language. Nobody speaks it; very few can read what examples of it we have, and then can only do so in a very limited way. It hasn't been figured out yet.

It's interesting to view the lists of dead or extinct languages which can be found in such sources as Wikipedia. What is striking about these lists is that the languages shown as dead or extinct significantly outnumber those which are "living." Dead or extinct languages may have been transformed over time and become living languages, as Latin became Italian, Spanish and French. Or they may have been annihilated in the course of cultural assimilation. The English and Americans insisted that the children of those they conquered learn English. They even thought they were doing them a favor by conspiring in the destruction of native languages. And of course they were not alone in this linguistic imperialism.

The extinction of a language is, I think, a real tragedy. So essential is language that it may be said not merely a people or a culture but an entire world is lost when this takes place, or at least a world view, i.e. how the world is perceived by a people, how they interact with it. It's a kind of genocide. The extinction of languages is something like the extinction of those who spoke it. If that's the case, then our history has been a series of extinction events; hundreds of cultures have been lost or destroyed, ways of living have been wiped off the planet.

English is neither dead nor extinct, of course, but it's interesting to speculate regarding whether it will be one or the other, in time. I think it's more likely it will be transformed. It may be that American English will be transformed through the slow progression in the use of Spanish in the U.S., which will take place regardless of the efforts of those who will, whether they like it or not, die soon enough and likely not be replaced or replaced by a steadily dwindling number of their descendants with the same reactionary views. Or, and this is especially interesting, it may be that English will be transformed by the technology which now encourages us to use it less and less.

It happens that technology at one time contributed to the use of language in the sense that it led to the growth of written language. Increasing sophistication in the use of tools to increase agriculture and the production of goods resulted in an increase in communities and transactions between them and individuals, which in turn fostered the development of means of written communication to express law and memorialize commercial transactions and eventually treaties, the use of numbers and signs to represent them, etc. Or so it's traditionally thought.

Now technology promotes the devolution of written language. Thus we're developing a kind of shorthand, a restricted form of English employing letters as words by virtue of the way they sound ("you" becomes "u"), the use of abbreviations which have become instantly recognizable (e.g. "lol"), and emojis. The day will come, I predict (for all I know it may be here) when poetry, prose, lyrics are crafted on the basis of such devices of language; we may develop a new kind of hieroglyphic language.

Old English died out long ago. What will be come of the English of today? The chances of it being superseded as it superseded other languages are slim, I believe, but its users and their technology could well render it radically different from what it is now.

Sunday, August 27, 2017

Pardons and Pandering

In our Glorious Republic, the authority of the president to grant pardons is itself granted by the Constitution. It is granted in Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of that remarkable document, which article, section and clause as well provides that the president shall be the commander in chief of the army and navy of the United States. and also indicates that the president has what are normally referred to as "executive powers." The pardon power is simply stated. The president "shall have the power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States, except in cases of impeachment."

The pardon power is sometimes treated as silly, as in the case of traditional pardons issued to a single turkey each Thanksgiving. Harry Truman is shown exercising that power, above. Speaking as a lawyer who has practiced for decades, this power is one that has always concerned me. I have no idea when or why presidents began pardoning turkeys, but wish that they had been given power to pardon turkeys only. For example, the Constitution could be amended to say presidents "have the power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the United States by turkeys."

Granted, the drafters of the Constitution likely didn't anticipate that a person as ignorant and corrupt as the current office holder would be elected, or even could be elected. Granted also that the power to pardon has been deemed to be one of the powers held by heads of state such as kings and emperors of the past. Even so, I find it hard to think of such a power, left unlimited as it seems to be in the Constitution (except in cases of impeachment), as providing for anything but corruption and favoritism.

Fortunately, the power has been tempered by custom and practice. Usually, the power is reserved until the end of a president's term of office, when presumably there would be fewer pockets to line, less political bills to pay. Possibly, the president may even by that time have learned something about the misuse of power and the benefits of being circumspect. Also, the Justice Department is usually consulted in the process. Consideration is given to whether the public welfare would be benefited or at least unharmed if a pardon was granted, whether the sentence imposed was severe, whether the person pardoned has expressed remorse, whether evidence indicates conviction was tainted in some manner, and such other aspects of a case as might occur to a reasonable person trying to make a reasonable decision.

Sadly, in this most recent case the pardoner is neither reasonable nor, it would seem, interested in making a reasonable decision. It seems that the president failed to consult with the Justice Department beyond asking it to drop charges (as it seems is his wont). It seems indeed that very little was considered beyond the fact that person pardoned was an avid fan of the president, held views similar to those held by him regarding immigration,, was elderly. and was the kind of person admired by those who admire and support the president.

Even a more competent or less corrupt president might be expected to favor pardoning friends, families and allies, however, and be tempted to use the pardon power to their benefit. The fact that kings and emperors of the past had such power would seem to me to be more a reason to withhold it than assign it to any one person, most kings and emperors having been less than wise. It would be best if there was no such power. But it's likely that this power will not be revoked by Constitutional amendment, and the best that can be expected is a limitation of the power.

If the drafters of the Constitution were unable to envision the mess we are in now, or predict that so sorry a person would one day hold the office of president, their lack of foresight is unfortunate but understandable. Men of the kind they were didn't consort with men of the kind we have now in office. We, though, cannot be excused if we expect anything better from such a man, who may be expected to pardon his friends and family if it is found that they engaged in criminal conduct, and especially to pardon himself should it prove expedient.

We may hope that no other such person will become president in the future, but to expect that will be the case is foolish. If we're capable of electing our current president, we're capable of electing most anyone. So, I think the public welfare would be served if the pardon power was expressly restricted to certain limited types of crime, that certain standards be met and that a president be required to consult with Congress before a pardon is granted.

The Executive Branch has become too powerful in various respects, especially when it comes to exercising war powers. Limitations on that power are needed if we must expect that in the future unworthy and incompetent folk will be elected president.

Saturday, August 19, 2017

Statues and History

Statues have been much in the news, lately. Not the one pictured above, but others. The one pictured above is of Henry IV of France. Not very popular among his people while he lived, he was honored after his death for his achievements. His statue as well as those of other kings was torn down during the French Revolution. It was rebuilt, however, in 1818, and continues to stand where it stands now, as pictured.

I've never been much inspired by statues, or even interested in them, except as works of art or as historical artifacts. I mean by "historical artifacts" in the case of statues those which tell us something about a period of history. Those are generally ancient, and sometimes religious.

The statues in the news these days, which people are inclined to remove or destroy, and which other people wish to preserve and keep in situ, are statues which are of Confederate generals or heroes. Like statues of Union generals and heroes, they themselves tell us nothing significant about history. Neither are they works of art. They depict people who lived, who are considered significant figures of history by those that erect them. They're generally meant to honor those they depict.

Those like our increasingly tiresome president who consider them part of our history are mistaken, I think, unless they mean to say that they've been in place for some time, which is so trivial a statement I assume that it isn't intended. When we speak of the history of the United States, I don't think we refer to statues.

For good or ill, I tend to ignore such statues. I know they're there when I encounter them, I may know without encountering them that they stand in certain places. I'm not interested in them. They may be taken down for all I care, or they may remain for all I care. They don't inspire any kind of emotion in me, or at least have not in the past.

For my part, I think there's nothing admirable about the Confederacy. So, I find it hard to understand why such statues exist. Those who are depicted by them may have been skillful military commanders; they may have been brave. But, they used that skill and courage in the service of a rebellion against their country, and in the service of a regime which had as its purpose the preservation of a horrible, contemptible, institution.

I therefore am not in the least concerned by their removal. And I think it unreasonable to claim, as some apparently do, that it's important that they remain. To the extent they have any significance, they are significant only as symbolic of a pro-slavery rebellion against lawful authority. Those who think that should be honored are unworthy. Those who think it should not be honored are right.

It interesting to note, though, that these statues may come to have historical significance depending on what happens now that there's an outcry against them. If they're torn down or removed, it may reflect a change in our perception of our history, which will in itself be historic. On the other hand, it they're permitted to stand or their removal is prohibited, it may reflect a perpetuation of what has been--in my case--indifference and what has been in other cases an admiration of, and perhaps nostalgia for, a hateful institution or a fundamentally racist ideology.

Does the history of the statue of Henry IV suggest, however, that statues will be erected, removed, and re-erected as times and people change? Does our idea of what is or is not honorable or admirable change over time? It certainly has in the past. In this case, it should not.

Monday, August 14, 2017

Of Job and Flies

It seems boys tore the wings off of flies in the 16th century just as some likely do now. Do the gods (still?) kill us for their sport? So thought the Duke of Gloucester in Shakespeare's King Lear, a kind of response, or riposte I sometimes think, to the Book of Job--or perhaps merely a parry.

It sometimes seems they do, life and our grotesquely selfish propensities given what they are, and one can see why someone believing in a personal, oddly Earth-bound or human-bound god or gods might think so. Except of course for Job. Much has been made of his faith, his trust, in God while writhing in the "fell clutch of circumstance" at which we lesser sorts wince and cry aloud. Lesser sorts than Job, in any case, and it appears the Victorian William Henley or his narrator in his poem Invictus.

Someone, somewhere, sometime, must have considered whether Job may be called a Stoic, and (who knows?) whether Henley was one or was trying to portray a Stoic point of view in his poem. That poem is, unfortunately, forever associated with mass murderer Timothy McVeigh, and his infatuation with it seems to me to disqualify it from being Stoic and to emphasize that it cannot have been written by a Stoic. McVeigh certainly was not one, as he could never have killed and maimed all those he did if he was a Stoic, and the characterization of the world as a darkness black as the pit, full of wrath and tears, and circumstances as fell, is not at all Stoic, either.

And Job? Job's not a Stoic, I think; not a Stoic Sage, in any case. Nor is his God one that a Stoic could believe in.

A Stoic would find it impossible to believe in a God who tests his creatures by setting Satan loose on them. That's a very personal God indeed and one that intervenes in life and the world, in this case to wreck havoc. The Stoic God, I think, is life and the world or perhaps better thought of as the soul or intelligence of life and the world.

The Book of Job properly notes that we humans do not think from the perspective of the cosmos, and may "explain" that what we believe to be evil is not such from the cosmic perspective (I say "may" because it's unclear, the God of Job not being inclined to explain why Satan was allowed to heap misfortune upon him). But that doesn't quite do the trick either. Job doesn't seek to consider things from the cosmic perspective. How can he, and believe in the God he believes in? His God apparently doesn't see things from the cosmic perspective either. If he did, he wouldn't tell Satan to torment Job, nor would he honor Job and rain blessings and material goods upon him after he passed the "test" and repented for questioning God if not failing to worship him.

Once again, I'll write to say that I think what most distinguishes Stoicism is the perception that we should not concern ourselves with things not in our control. What happens to Job is the result of things undoubtedly outside of his control. He seems to have understood this superficially, but had he been a Stoic Sage, if not an aspiring Stoic, he not only would have resigned himself to them he would not have attributed to them any particular meaning as he wouldn't have thought of them as being peculiarly directed towards him. There are no victims in Stoicism. There simply is what there is, and our part is to do the best we can with what is in our power. This is Stoicism regardless of whether Nature or Providence or God is thought good or bad, regardless of whether there is evil or good.

Evil or good is something we do, not the universe. We do evil when we desire or are disturbed by things beyond our control. The things we desire (which include people) or are disturbed by exist, as we do, as part of the universe, but our desire for them or fear of them is within our control, and it's that desire or fear which in turn generate evil in the form of our greed, hate, violence, cruelty, and all our passions.

Our likes and dislikes aren't the concern of the cosmos, nor are our needs. Those are defined by our interaction with the universe of which we're a part. The "test" we're subject to is this interaction, but it isn't a test put to us by some deity or demon. It's what it is to be a living part of the living universe. Do we live intelligently or do we not? Do we seek to have or avoid what isn't in our control or do we not, instead acting reasonably with what is in our power?

Stoics aren't as flies to wanton boys, nor are they Jobs.

Sunday, August 6, 2017

Apocalypse None

The Gospel of Mark is thought to be the oldest of the four Gospels which have been accepted by the Church and, it seems, Protestant churches as well. As we know, there are other gospels which were unaccepted, if not purged, by the early Church and thus excluded from the canon. The reasons for their exclusion makes an interesting study.

The Gospel of Mark is interesting in itself though. In its original form, it didn't include what is included in other Gospels, particularly when it comes to appearances of Jesus after the Redemption. It also includes statements it states were made by Jesus regarding what's generally described as the Second Coming and the commencement of the Kingdom of God which are considered troubling to many Christians. Those statements are to the effect that it will occur during the lives of those to whom he spoke, or within a generation (e.g. Mark 9:1).

Early Roman critics of Christianity, such as Celsus, noted this and other peculiarities and inconsistencies in the Gospels. They also noted that at the time they wrote, those who heard Jesus speak these words and their generation had long since passed away, and the world continued on nonetheless just as it had for centuries. They reasonably inferred from this that Jesus must have been a false prophet if not something worse.

No less a zealous apologist for Christianity than C.S. Lewis felt that this is most "embarrassing" passage in the Bible. Earlier apologists were also well aware that the Gospel ascribed to Mark was a problem in various respects. Origen wrote a book to refute Celsus, though it's thought he didn't do a very good job.

Christians and Christianity have struggled over the long years to account for the Gospel of Mark. It was maintained at one time that this Gospel was a mere summary of the Gospel of Matthew, and less important. Naturally, it couldn't be maintained that the Gospel of Mark was wrong, or inaccurate in any sense, if it was thought to be the Word of God. But the fact that the available evidence indicates it was written before the other Gospels makes this explanation unhelpful.

And so rather than accepting that it's possible the words of the Gospel of Mark should be taken to mean what they clearly say, which would be to acknowledge that Jesus was wrong and so could not be God, those words have been the subject of interpretation. For example, it's been claimed that what Jesus spoke of according to Mark was something different from the real Second Coming, but a spiritual one resulting from his death on the cross or his Resurrection, or was somehow intended to refer to the destruction of the Jewish Temple by the Romans in 70 C.E.

The Romans certainly destroyed the Temple. I've now seen "with my own eyes" the Arch of Titus and the relief on it showing men of the legions marching in triumph holding the riches of the Temple. But it isn't clear to me why Jesus wouldn't simply have said that was what he was referring to, nor do I see how the Kingdom of God came to be established due to the sacking of Jerusalem.

Ancient writings, such as those of the obliging pet of the Flavian emperors, Josephus, tell us that the Roman world and especially Palestine were host to a number of men who worked miracles and taught that the end of the world was coming. Jesus thus was not unique in that respect. It appears such men are not unique in our history, as there have always been those who proclaim the end of the world is nigh for one reason or another. There are such men today, in fact, and like their successors they've found that they have admirers enough to keep them happy, and even wealthy though not wise.

I don't know enough of religions besides Christianity to say whether this ecstatic belief that the world will end and only certain of us will be saved is characteristic of religious belief everywhere, or limited to the various kinds of Christians. Christians, though, have too often believed someone to be a prophet and have anxiously awaited the end of others, but not themselves. Periodically they venture to some place or other, gathering at the appropriate time to witness the Second Coming, only to be disappointed. Their prophet generally explains thereafter that he was wrong in his count, or misinterpreted signs given, and comes up with another date which in turn is found not to be the day the world ends or Jesus comes again.

This isn't all that surprising. But what is surprising is that the people disappointed in their expectation of annihilation blithely accept explanations offered and believe that the end will come at whatever new date is selected by their erring leaders.

This kind of faith, if it may be so called, is difficult to explain. The faith in an apocalypse must be very stubborn to survive continuing disappointment and the relentless survival of the world and its sinning inhabitants. Mere stupidity can't provide the only explanation. The hope for an end of the world must be extreme.

The world is a difficult place to live, but it's probably now a less cruel place than it was for the poor and disaffected of the Roman Empire nearly 2,000 years ago. What is it in some of us that provokes such an enormous discontent, such a fervent dissatisfaction with the world and with other people, that we hope and pray that the world will be destroyed and most of us swept away by an angry god?t

The Gospel of Mark makes me wonder about how the early Church grew and Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire. As those who expected the Kingdom of God to commence while they were still alive noticed that it had not arrived, did they come to question whether Jesus was God? There are statements in Paul's letters which indicate he was aware of this possibility and spoke against it, even as he spoke against those followers of Christ who were too Jewish to accept that he was the (self-proclaimed) apostle appointed by God. Is the Christianity we know that of Paul and not that of Jesus? That isn't a new notion by any means.

Would Christianity have spread if Jesus was portrayed only as he is in the Gospel of Mark, in its original form? In other words, would it have come to dominate the Western World without the later Gospels, the Acts, and the writings and travels of Paul, who never knew him while he was alive? Or would it remain what pagans thought it was initially, a Jewish sect?

Regardless, we can see in this expectation of and hope for the end of the world, the thirst for martyrdom, and the reverence for the relics of saints which began very early, why educated Romans (like Marcus Aurelius) thought the Christians to be irrational and irresponsible, and even insane, and why the Emperor Julian and others thought Christianity to be a death cult.

Thursday, July 27, 2017

A Stay in Bedlam

It's unclear whether we're inmates or visitors, but I think we've reached the place. Let us go then, you and I, into Bedlam.

It's said Bedlam is another name for Bethlehem Royal Hospital, an institution for the insane which was around for quite some time; the oldest such place by repute. It's infamous for many reasons, but perhaps it's most notorious because it put the mentally ill or those who were thought to be mentally ill on display, to paying visitors. It was a kind of human zoo, though those behind its bars were likely never treated as well as animals are in the better zoos we have now. This post is graced by one of the prints of Hogarth's series of works called The Rake's Progress, showing the decline of a good-for-nothing son of a rich merchant, who ends up in Bedlam, eventually. Served him right.

"Bedlam" the word as opposed to the institution has come to mean a scene of chaos or mad confusion. Perhaps it's just me, but this is what I've come to think the politics of our Great Republic has become. The spectacle is sometimes amusing in a grotesque fashion. I like to think, and hope, that I'm an observer and not a resident. I suspect I feel in those moments of amusement something along the lines of what visitors to Bedlam felt--a combination of embarrassment, amazement, distress and shameful enjoyment of the oddities who appear before me as I walk, if a viewer of TV or user of a computer can be said to walk, through the madhouse or rather the madhouses which are Congress and the White House.

How did it come to this? Was it inevitable that our Glorious Union would come to be presided over by an ignorant, venal lout, and be represented by craven and equally venal lackeys of special interests? Old Ben Franklin may have been right when he surmised that we would eventually become so corrupt as to require a despotic government. We have as Chief Executive someone it seems would like to be a despot, is used to being one in his privately-owned business, but I think we're more a plutocracy than anything else.

Aldous Huxley and George Orwell not all that long ago created their very different dystopian visions of what they thought we and our masters might, or were likely, to become. Neither of those visions, though, envisioned or encompassed a government by the obnoxious, for the obnoxious and of the obnoxious. How else can we describe those who believe themselves to be our leaders? Orwell, perhaps, came closer to the truth in his Animal Farm where pigs and humans become the same sad, selfish creatures.

My hopes for the government of our future are minimal. I have no expectation of greatness or achievement by our leaders. I merely hope to be left alone. A solitary confinement, call it, in one of the cells, free for the most part from interference any more invasive than the yammering and posturing we can't escape from, really, in this world where the show is always going on and there is no respite.

Sunday, July 23, 2017

Idol Speculation

It's said that successful demagogues grasp more than others the fact that people when part of a group are manipulated not by reason or argument but by an appeal to emotion and the mere repetition of an easily stated proposition or better yet a claim...an utterly unsupported assertion that is known to appeal to them. It may appeal to them for various reasons. It may be something they desire to be true, it may be something for which they seek assurance, it may be something they want to do or see happen for elemental reasons.

Not surprisingly, those who are successful demagogues are also prized by those they so manipulate. They say what their audience thinks or better yet wants to think, believe or want to believe. Also, they relieve their audience from the need to think. Thinking being onerous, it's easily dispensed with, eagerly put aside. Why think when all is so clear? Why think when someone has already thought, and to your liking, on a matter important to you?