A CICERONIAN LAWYER'S MUSINGS ON LAW, PHILOSOPHY, CURRENT AFFAIRS, LITERATURE, HISTORY AND LIVING LIFE SECUNDUM NATURAM

Sunday, November 26, 2017

Selfishess, Salvation and the Supernatural

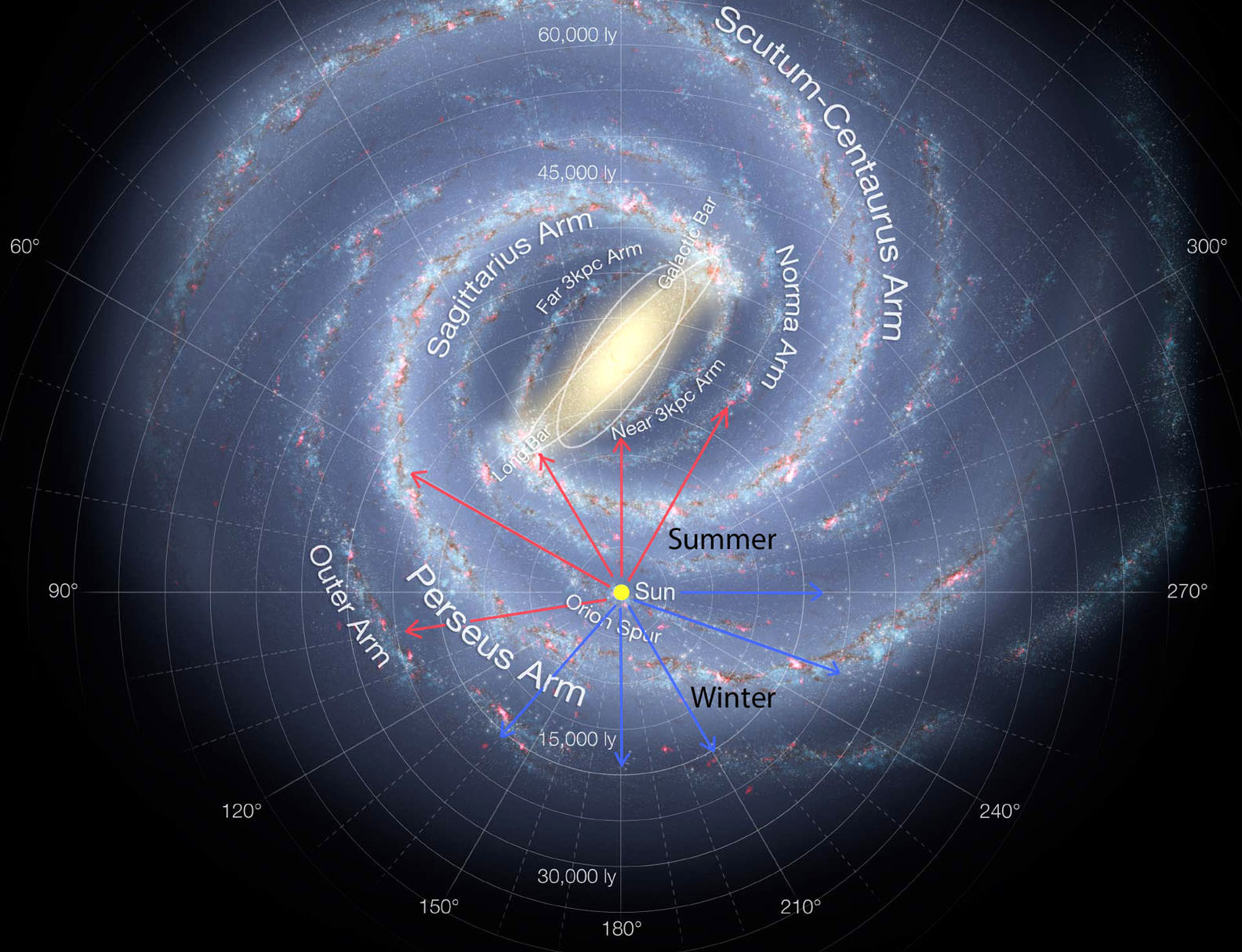

The Milky Way, the galaxy of which our world is but a tiny part, is itself only a tiny part of the unimaginably vast universe in which we and all we know exist. Why do some of us insist there is "more"?

There is certainly more than we know, of course. We know only a very little of the universe. What I wonder, though, is why some of us believe there is more than the universe--by which I mean more than nature, i.e. the supernatural.

That very odd man, Cardinal Newman, in his Apologia, I think, wrote that he felt from an early age that the real world we know isn't "really real" but that there was something else lurking behind it, as it were. I find this view as odd as the man himself, even odder. What we insist on calling "supernatural" seems to me to be very much like what we know in nature made or perceived as strange. Ghosts, for example, are eerie figures which were people and so resemble people or are people but in an unusual form. The transcendent God many believe is, apparently, the perfect form or creator of all that we creatures of nature find admirable; but what we find admirable we admire because we know or believe it to be so naturally--we encounter or experience it within nature.

It strikes me that what we believe to be supernatural is more easily conceived of as being part of nature, of the universe that is, but part of it that we don't yet know or understand. People ignorant of quantum physics too often refer to it as somehow establishing something or other. I'm certainly ignorant of it myself, but what little I read and comprehend of it seems bewildering enough to indicate that we have much more to learn about the universe. With so much more to learn, why do we purport to envision anything beyond it? How can we even guess what that might be?

I would guess that belief in the supernatural results from a dissatisfaction with the natural. That dissatisfaction can only be one arising from a very narrow point of view of nature. This is necessarily the case because it must arise from the perspective of a dissatisfied person.

There's certainly enough to be dissatisfied with, of course. It's likely that's always been the case, and likely as well that there was even more to be dissatisfied about in the past. But the fact remains that nature dissatisfies because our perspective of it is ultimately a selfish and, relatively speaking, small one. The supernatural being unnatural or a-natural doesn't disappoint or rather can't disappoint because it isn't real and may be anything we want it to be.

Dissatisfaction with the world is necessarily selfish, and so it isn't surprising that satisfaction with the supernatural--that which isn't part of the world and so cannot be attained until we're not part of the world--is selfish as well. In other words, the afterworld or otherworld where we go when we're out of nature is hoped to be what we would be satisfied with, unlike the world in which we now live. We're thought to attain this desirable afterworld if we're worthy; if we're saved. The reward for salvation is in that sense intensely selfish as well. We are saved. Others may be if they are saved; or they may not be.

So it seems to me, in any case, as part of this speculation or train of thought.

This emphasis on the supernatural, on the transcendent, is therefore an exceedingly personal one. Which to me raises the question whether it is truly moral.

Concern for the welfare of others is a concern which is properly directed towards living in nature. Concern for their "immortal souls" is a concern with the supernatural. Perhaps that's why we've always been less concerned with the lives of others than we purport to be or than we say we should be.

It isn't surprising that those who refuse to cherish nature believing it to be secondary and who maintain that we're apart from nature rather than a part of it should be supremely selfish, because the world and all that is in it is essentially not their concern. It cannot be, not "really." We suffer from a disregard of the universe though we barely comprehend it. Our belief in transcendence dooms us to disconnection with the world and others.

Friday, November 17, 2017

Of Cupidity and Stupidity

The quote above is from one of Shakespeare's lesser-known (to me, at least) plays, Troilus and Cressida, and is brought to mind by...what should it be called? A tsunami, an avalanche? In any case, the continuous claims of sexual harassment being made on what seems a daily basis here in our Great Republic against quite a few people, that is to say, against various men, by both men and women.

It seems rather remarkable even to me; a lawyer and therefore someone accustomed to and perhaps even dependent on wrongdoing of one kind or another (by others, of course). But even those of us who thrive on the misdeeds of humanity must admit to surprise at what seems to be a unique moment in tawdry history.

The law of sexual harassment has been around for quite some time, in the U.S. at least. It's something I've known of professionally and have had cause in my practice to become to be acquainted with, now and then, over the past several decades. One would think that employers and employees, in particular, would be aware of it and fear its application given the litigation and claims through state and federal administrative agencies which have taken place and the stern warnings lawyers and human resources types have issued for many years now.

So in one sense I find it puzzling that sexual misconduct of this kind is so apparently widespread. How can anyone be so blithely unconcerned by it? How can so many men indulge in it, that is to say, without fear of the consequences?

I also find it puzzling that there are those who feel that sexual harassment is, at least in some cases, something which shouldn't be of great concern, or can be excused as "boys being boys" or harmless play. The law is the law. It doesn't matter whether one agrees or disagrees with it, or whether it's thought of as too much or too little. It's foolish to be anything but prudent and so to respect it even if one doesn't respect those it's intended to protect.

But fools we tend to be, particularly where sex is concerned. I think that any more than casual observer of human conduct must acknowledge that lust, lechery, sexual desire--whatever it should be called--can render us extremely stupid. I think that particularly in the case of men it makes great, gaping idiots of us all unless we take steps to control our own desire. And, it's such a completely selfish, narrow and powerful desire or impulse that the consequences to ourselves and others are disregarded.

This isn't to justify sexual harassment let alone explain it, but to recognize that the urge behind it is there almost always and must be restrained. If it isn't, we do stupid, harmful, cruel, immoral things and should pay for it in one way or another.

Add to this the understandable concern victims have that making claims of sexual harassment will subject them to shame and ridicule and even have financial consequences if the perpetrator is powerful and influential, and it isn't so surprising that it goes unchecked in too many cases. It seems that could be changing, though.

Unfortunately, as Shakespeare or his character noted, lechery like war is always in fashion among us, and tolerated by us. It must remain to be seen whether sexual harassment will diminish as a result of the rising intolerance towards it or whether our remarkable lack of sense and control in this area will continue. I think it's a good sign that even those who have previously been given a pass, most ignominiously, in this area (yes, that former president for example) are being recognized and condemned as predators.

Given those accused, though, I wonder if older men are particularly prone to this behavior. Do older men act in this fashion because they know their failing looks and powers make it less and less likely anyone will want to have sex with them? It's been well said that there's no fool like an old fool.

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Sancta Mater Ecclesia

Holy Mother Church, or Sancta Mater Ecclesia in Latin. The One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, just as it's said, also in Latin, in the interesting picture above. Or, according to the inscription at the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, built at the order of the Emperor Constantine and dedicated in 324 C.E. by Pope Sylvester I, omnium urbis et orbis ecclesiarum mater et caput, the mother and head of all the churches in the city and the world.

Old Mother Church, in truth. Quite old, really, as age is measured in human history. As I've posted before, I have a sentimental fondness for it as it was at one time, during my youth. It gave a certain joy to my youth, as we as altar boys said its God did as we went to God's altar, or if not joy a kind of distinction.

It's curious how we refer to institutions, particularly those we look back upon in fondness, as "mother." We call our old schools Alma Mater. I suppose we can call Mother Church the same, as it can be said to have nourished us Catholics for a time. But nourished us in what exactly?

It must be admitted that one thing Mother Church encouraged, probably throughout its long history, is reason, or more particularly reasoning, as it was developed before the Church came to exist. That may seem an odd thing to say, given that the beliefs of Catholicism, taken literally, seem unreasonable. That's likely why they often are not taken literally, particularly by those believers who reason or employ reason in its defense.

Regardless, though, I think it fair to say that the Church has always honored reason and reasoning. The Church Fathers employed reasoning in condemning the pagans. Tertullian, a lawyer, knew reasoning in the form of rhetoric at least. That was a lawyer's tool, particularly in those times. The Church Fathers, like Augustine, knew their philosophy (pagan, of course) well, and were educated in the manner in which ancient pagans were educated and had been for centuries. The great pagan philosophers didn't take pagan religion literally, either. Why should Christian philosophers?

So, I think the early Church soon abandoned the position seemingly taken by Paul, rejecting the "wisdom of the wise." Instead, it accepted it; assimilated it, in fact, and made it serve the purposes of the Church.

I think its also fair to say that the Church has always honored culture, education, history. It kept the wisdom of the ancients alive, through the work of its monks, even if they functioned as mere scriveners, patiently copying the great works of the past. As a result it fostered great thinkers even during what are called the Dark Ages; Abelard, Duns Scotus, Aquinas, Bonaventure, William of Ockham; it's an impressive list. It borrowed from the heathen as needed in order to do so, and so rediscovered Aristotle via learned Moslems. Aristotle so impressed churchmen he was called "The Philosopher." Thomas Aquinas famously modified Aristotelian thought so as to make it the foundation of Catholic philosophy--known as Thomism. It still has its adherents today.

For these services Mother Church deserves honor. I wonder, though, if in inculcating its sons and daughters with a love or reasoning, culture, history and education Old Mother Church gave her children the learning needed to lead them to think her cupboard of reason was, ultimately, bare, as that of Old Mother Hubbard was bare of nourishment.

Learning can be dangerous to a religion, especially when learning involves fostering the capacity to reason, to think logically, to ask questions. Eventually, those questions address the fundamental premises of Catholicism and Christianity, e.g. the divinity of Jesus, Original Sin, Heaven and Hell, the Trinity, the redeeming character of the sacraments, transubstantiation. What could be their justification? How can they be justified, in modern times? How could Jesus be both God and man? What sense does the seemingly endless list of sins, so specific to human beings, and a belief in a God-man, make given the vastness of the universe and given that our world is such a tiny, tiny part of it?

To someone trained to reason, recourse to revelation and faith is unpersuasive. It's a kind of resignation.

Mother Church certainly has managed to survive for centuries, so perhaps it hasn't arranged its own destruction after all. Perhaps it hasn't undermined the fundamental beliefs which make it distinctive. But it seems to me that it does, necessarily. And so a choice must be made, to be Catholic by disregarding reason or accepting that fundamental beliefs or premises are not to be "taken literally." But that, it seems to me, is to accept a Catholicism, a Christianity, which has lost all which makes it distinctive.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)