A CICERONIAN LAWYER'S MUSINGS ON LAW, PHILOSOPHY, CURRENT AFFAIRS, LITERATURE, HISTORY AND LIVING LIFE SECUNDUM NATURAM

Monday, December 17, 2018

Intolerance, Exclusivity and the Heirs of Abraham

A thread on a forum I frequent has motivated me to wonder something about the so-called Abrahamic religions, i.e. those which look back to the patriarch Abraham as a founder, directly or indirectly. What I wonder about them may strike some as disturbing or even blasphemous. I wonder whether there is anything peculiarly good about them; whether, in other words, they in themselves contain or preach anything good, that hasn't as it were been borrowed or assimilated in the course of their histories from elsewhere.

Above is a picture in stained glass, I think, depicting Abraham about to sacrifice his son in accordance with the will of his God. I sometimes think of the God of the Old Testament as a kind of colossal, unsleeping cat, toying with his creation as a cat would a mouse. A cat without a cat's usual charm and grace, though, and without its vast capacity to sleep, and doing no harm by doing so. Whether urging the chosen people to destroy the Canaanites and take their land, laying waste to entire cities, flooding the world, or playing torturous games with Abraham and Job, he's perpetually doing something to us. He seemingly made us to be the objects of his whims.

A particular belief in a particular God has been the cause of much violence and many wars, it's true. But was it so, is it so, when one of the Abrahamic religions is not involved? As far as I know, the pagans of the ancient Mediterranean didn't war against each other because one group worshipped Isis and one Mithras, for example. Tolerance of religious beliefs was characteristic of the Greco-Roman world, except, of course, when it came to the Jews and Christians.

Greeks and Jews we know rioted against each other in Alexandria. Roman suppression of the Jews in the two "Jewish wars" was ruthless. The Roman state, periodically and with varying degrees of seriousness, persecuted Christians, but with nowhere near the seriousness depicted by Hollywood and others. But violence against Jews and Christians was not motivated by the fact that they believed in Yahweh or Jesus as opposed to one or several of the pagan gods. It was motivated by the fact that they believed themselves to be exclusively in possession of that which is right and good by virtue of the fact they worshipped their particular god and refused to recognize as right and good and indeed despised anything they did not think right and good--including pagans, the Roman state, and pagan institutions. They were considered anti-social, as they were against pagan society and culture. They appeared to subvert society, traditional religion and the government.

Jews and Christians were exclusive, sometimes militantly so, and intolerant. Once Rome became a Christian Empire, it persecuted pagans far more relentlessly and effectively that the pagan empire persecuted Christians. Islam, once founded, was similarly exclusive and intolerant, and engaged in great conquests in the name of its God. Christianity was an imperial force as well. All over the world, people were "saved" by being made Christian.

There are works of art inspired by religion, and they can be said to be goods peculiar to particular religious beliefs. What of wisdom or ethics can be said to have resulted only by virtue of the Abrahamic religions, however?

I would say nothing, not really. All that was or could be said on those topics was said before Christianity or Islam existed, and developed independent of Judaism, primarily due to the ancient Greeks. If one discounts unsubstantiated claims such as Plato or Solon got lessons from Moses, there's nothing to indicate the Greeks were influenced by Judaism in any significant respect. That Christianity borrowed extensively from pagan philosophy is clear.

It's often claimed that Christianity brought with it the idea of love, something said to be absent from paganism. Readers of Plato's Symposium might find that surprising. But Christian love has much more often than not merely been given lip service. If there was such a teaching, it's been ignored as a practical matter. And arguably, the love touted by Christianity has never been capable of realization. One simply does not love everyone. Respect and dignity were accorded to all by the pagan philosophers; a much more achievable goal.

Well, that's what wondering can do. But what can be expected from religions which hold themselves out to be the only way to God, the only way to worship God, but conflict in the name of God until all believe the same?

Labels:

Abraham,

Christianity,

Islam,

Judaism,

Mithras,

Plato,

Solon Isis

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

The Unending Past

It occurs to me that the past is never past. Not, at least, in the sense that it ends, or is done. The past is ever growing. It is never over, never finished, and becomes larger--and more imposing--with each moment.

We may of course, if we wish, distinguish it from the present. What we experience, think, feel and do now isn't part of the past, but will be in an instant. Like all else that we experience, think, feel and do, then it will be beyond us and unalterable. We may do now things which will alter or correct the consequences of what took place in the past, but what happened has happened and cannot be changed.

This is a misfortune. What we are is necessarily due to the past, what we will be and what we will do is necessarily formed by the past. We're entrapped by it, to a certain extent at least. We're slaves to the past. More often than not, we'd like to change it, and are barred from doing so by time's arrow.

The past is what we regret; it is all that we regret, obviously. We're unable to regret what hasn't taken place. As we're constantly reminded of the past, by people who speak of it or by places where something occurred, regret is a part of our lives unless we've done nothing to regret, ever. No human being can make that claim, unless delusional.

Even if we're not reminded in waking life, though, it lurks within us and is resurrected in a peculiar way in dreams. Just last night I dreamt of something I regret, something which took place long ago, something which I regret so profoundly that it appears in dreams in some form or other, not frequently but all too often, and I regret it all over again; regret it as I did when I first learned of it. I say "in one form or other" because the dreams aren't reenactments of what I regret, but odd vignettes, pictures or dream-events which derive from the regret.

It was something I wanted to take place and did not. As a result, something else took place.

It's hard to conceive of anything more futile than regret, or explain the pain of dreams that provoke it and bring to a kind of half-life that which is regretted. But such is the nature of the past that dreams can't be avoided, Also, that which is now isn't what would have been, and the contrast is impossible to ignore, so waking life will also bring regret if we let it.

The unchangeable past is clearly beyond our control. An aspiring Stoic, therefore, should be indifferent to it and not allow it to disturb him. But the past is unending, and grows for each of us as we age. The past is the most formidable obstacle to our tranquility. It doesn't altogether help to understand it isn't something within our power, however, because we forever wish that it was, and can't prevent it from haunting us in our dreams.

Monday, December 3, 2018

There's Something About "Hamilton"

There's something about it, I think, that would explain its success and also explain why I wonder at it...and its success. I don't mean to say that as musical theatre goes, it's bad. We speak after all of entertainment, and that which entertains always has a value unless it corrupts. There is no corruption here. There is, instead, an overwhelming but unsatisfying sincerity.

I should admit that historical inaccuracy concerns me. So, for that matter, does incongruity unless it is humorous, as it is in the case of farce, for example. One can argue that incongruity, inaccuracy and humor are to be expected when history is put on stage, and there is an element of truth in that argument. But when they're combined with sincerity, a problem results. It's not possible to be sincerely inaccurate. It's possible to sincerely strive to make a point and to do so while being deliberately inaccurate, though. Accuracy in that case is avoided in an effort to make a moral point, or to engage in propaganda.

Looked at as a piece of musical theatre of the Broadway type, I would describe that portion of it which precedes the intermission as manic. I'm not a fan of rap, but would think that even a fan would recognize that an effort is being made to compress decades into an hour or so, and that this numbs the mind and the senses. We seem to race through time; there are no stops, no pauses. It's like listening to someone doing an extended drum roll. After intermission, things slow down. There are actual melodies, but to me there is nothing memorable in them. Usually when exiting a musical I find I can remember one or two songs fairly well. That was not the case, for me, with Hamilton.

The inaccuracies are more galling than outrageous. For example, Hamilton (the person, I mean) participated in more than one duel. The cause of one of them is addressed--the affair with Mrs. Reynolds. Jefferson, Madison and Burr didn't confront Hamilton about his adultery, though. James Monroe did, and Hamilton challenged Monroe to a duel over it. Aaron Burr brought about a reconciliation between the two, however, and a duel was avoided. Presumably, the creator felt it was necessary to concoct some confrontation that didn't take place, and say nothing of Burr's friendly efforts, but I have no idea why; unless it was to show Burr, Jefferson and Madison in a bad light.

Incongruity as humor, or farce, is evidenced in the person of George III, and he thereby became my favorite character as he was certainly the silliest. I longed for the silly. Incongruity as humorless, however, was evidenced by the fact that in the case of this particular performance, virtually every historical figure known to have been white was played by a black actor. Is this wrong? No, but it's inaccurate and incongruous. One can't help but wonder what the reaction would be if white actors played historical figures known to be black. I think it would have been exceedingly negative. Why is it otherwise when black actors play white characters? Certain actors no doubt are given opportunities they wouldn't normally have. That is fine. But it would seem to me to be better in trying to create opportunities to create new roles, new plays, rather than bringing history to the stage.

The sincerity of the effort can't be doubted, but sincerity can be deceiving, in the sense that it induces some to accept inaccuracies as accurate. I can't help but wonder how many feel that what appears on stage here is all of it historically accurate. They shouldn't, I know, as this is theatre, and for that reason I'm more annoyed by the inaccuracies than outraged by them. But in depicting history we should strive to be accurate. Otherwise, people like Oliver Stone are free to indulge in fantasy and portray it as history.

Maybe I've read too much Santayana and Orwell, but I'm sensitive to games we play with history just as I'm sensitive to claims that history cannot be known, which itself encourages gaming. But it can be known, to a reasonable degree of certainty, and must be known if we're to learn from it and know what we are and how we became what we are.

Hamilton is so popular that I assume what I write about it will be unpopular, if indeed it's read. I don't begrudge it its popularity as a piece of theatre, though I found it less than overwhelming and not worth the ridiculously high price of admission. I merely hope it's thought of as no more than that, and not as history especially.

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Danse Macabre

I first became familiar with the Danse Macabre through the music of Saint-Saens, who wrote a tone poem by that name. I thought it a rather jaunty tune, though in a minor key and so thereby a bit unusual, perhaps even grotesque but in an entertaining manner. I didn't know when I first heard and enjoyed it that it was greeted with something approaching outrage when it was first performed; something I find difficult to believe, but all too believable.

I knew enough even at the time I first heard it to be aware of its association with death. Perhaps it's jauntiness in that association is what critics and audiences alike objected to in the 19th century. The use of a xylophone must have been particularly irritating back then. But it is after all a dance, even if a dance led by Death, and it seems that dance involved hopping or skipping judging from paintings, engravings and drawings by which it was depicted. So it seems to me "jaunty" well describes the part of Death in it, at least, cavorting as it leads us into....what?

In the Middle Ages when it seems the dance appeared as an object of artistic representation which became, if we can use the word, "popular", the dance as represented had much the same features everywhere it was displayed. A skeleton or skeletons, sometimes decked out in the garb we associate with the Grim Reaper, leads men and women and children identifiable by their dress as Emperors, Kings, Popes, Bishops, nobility, merchants and peasants--all of the kinds of people of Europe at the time--in the dance of death. The meaning and purpose of these works is clear enough. We will all die, and will do so regardless of our status when alive. Being one of the rich and mighty won't protect us from our inevitable dissolution. We all come to the same end, die and decay.

At that stage of humanity's "progress" death was more familiar than it is now. Life spans were short, medicine primitive, sickness rampant. The Black Plague and other diseases ran through whole communities. There was no escape from death. There's no escape now, of course, but seldom was the phrase "here today, gone tomorrow" more applicable.

Clear enough what was meant, then. But what was the reaction to the message? Reaction would vary, one would think. In pagan times it likely meant something different. There are old Roman funeral inscriptions which state one reaction; that is, to eat, drink and be merry while we can. That may have been the reaction of some in the Middle Ages as well. But with the advent of Christianity came a different view of the Danse. Eating, drinking and being merry were frowned upon at least to a certain extent; to the extent, that is, they were sins or caused sins to take place. And so the Danse impressed on many the need to pray for forgiveness, to repent, perhaps even to do good deeds. This would not be thought to do much if any good, though, in some circles, where only those were saved who were saved by the grace of God, not their own acts. Also, of course, there would be the reaction that one must do right by the Church and its rules.

In both pagan and Christian times, however, there must have been those few who reacted to the Danse as indicating the vanity of our concerns and actions, All fame, power and money came to nought. Marcus Aurelius wrote more than once of the fact that our words and deeds will not be remembered in the future and meant nothing to the world, which we may now call the universe.

How react to the Danse now, though? Some no doubt react now as others did then. Some would react like Marcus did. Most Stoics would know what he knew. To a Stoic it would serve as a reminder that we should treat things beyond the control of our will as indifferent. To do as Epictetus said, and do the best we can with what we have and take the rest as it comes. To understand that our deaths are according to nature, and not to be feared. Instead to be accepted.

But this time is peculiar in its selfishness, I think. At least, I think that's the case here in our Great Republic. We're encouraged not to care about others--and certainly not to do anything for them. Particularly those who are different. It's perfectly all right with many of us that some are poor, or can't afford health care, etc. Perhaps it's our Protestant background, and the myth of rugged individualism that make us uncaring. Or, perhaps we merely resent that others may get something we don't have "for free."

Our selfishness causes a different reaction to the Danse. I think that reaction is anger. We're angry that we, and what we want, will end. For some of us, that makes it easy enough to do violence, to others.

Thursday, October 11, 2018

Bad Advice and Consent

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution of our Glorious Republic provides that the President shall nominate, and "by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate" shall appoint, Judges of the Supreme Court "and all other Officers of the United States." This is often referred to as "the Advice and Consent Clause." We many, we unfortunate many, have witnessed the lugubrious exercise of this function by the Senate regarding the ascension (if that is a word that can be used) of a Judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Besides being a clause, Advice and Consent is also the name of a movie made in the early 1960s, presumably based on a book, starring Henry Fonda, Charles Laughton and other worthies regarding the nomination of a man to serve as Secretary of State. In that movie, the nominee was accused of being a Communist or former Communist; a satisfyingly serious condemnation given the times. The Senate revealed in the movie is a fictional Senate, of course, but either through the magic of film and art or otherwise that Senate--though portrayed as corrupt in a fashion--seems possessed of a dignity lacking in the real thing of our time. On this and on other occasions our politicians and our political institutions have demonstrated that truth can be far stranger, or at least seedier, than fiction.

Perhaps "stranger" isn't an appropriate word in this case. Sadly, there was nothing strange about the proceedings. They seemed very familiar, in fact. Posturing, hypocrisy, self-righteousness, scheming, lying is to be expected whenever our politicians are on public display and particularly when they are in groups. They scheme and lie in private as well, of course, but may be less inclined to posturing, hypocrisy and self-righteousness when not in the public eye. Be that as it may, the proceedings were by all accounts spectacular; a spectacle, in fact. I avoided them as much as possible, but a real effort is required to avoid anything that our dread enemy, the media, finds interesting.

What little I saw was disturbing in a peculiar way. Events were taking place; people were talking, asking and answering questions, but it was difficult to think of it as something which was not a movie or play. I wonder if that is how we experience events in which we're not directly involved. We watch a movie, generally a boring, bad one. Perhaps, but the feeling in this instance may have had its basis in the knowledge that the outcome of the proceedings was virtually certain. I think everyone knew that the needed number of members of the Senate would consent to the appointment from the very start, regardless of what was said, simply because the majority of members of the Senate are Republican. The only real question was how the Republicans would contrive to nominate while appearing to take seriously the allegations which were made, and whether they could do so while increasing their political status and likelihood of reelection--ultimately, the only concerns of politicians.

The Democrats like any other person of middling intelligence knew that the nomination would very likely occur, and so knowing that did what they could to attack the integrity of the nomination. Perhaps, also, they saw it as an opportunity to bring attention to the plight of victims of sexual assault, but I suspect that their primary end in view was to make their Republican colleagues look bad, which was at least achievable.

I won't delve into questions of credibility. I think it clear enough that the Judge drank excessively in his younger days, and marvel somewhat that he took pains to deny this, or at least not to admit it. That appears to have been the only well-established fact. So, he was less than credible in that respect, and much of his expressed outrage in the proceedings seemed a performance, similar to that of Senator Graham. This doesn't mean he committed sexual assault, however. Senate Committee proceedings are not useful in determining criminal conduct.

What I find interesting, and disheartening, is that the process has become so partisan, so infused with political conflict, histrionics and melodrama that it is doubtful whether it serves any useful purpose in assuring that competent people are appointed in any capacity as Officers of the United States. What competent, honorable person would want to subject himself/herself to such a review, given that the review would be conducted by people whose motivation is not assuring that the best person for the job is appointed, but furthering a political agenda at whatever cost? Chances are the only person who would go through it would be so eager for power that they're willing to expose themselves, to run the gauntlet.

The Senate can still consent, and will no doubt continue to do so, but is no longer capable of giving advice. But considering that currently, the one who is suppose to be advised is inadvisable, that may not be much of a concern in the short run.

Thursday, September 27, 2018

Invincible Ignorance

"Invincible ignorance" has at least two meanings. In Catholic theology, it refers to the state, or condition, of persons who are ignorant of Jesus because their circumstances are such that they are, or were, unable to know him. Among those who possess invincible ignorance according to the Church are pagans who lived before him--especially worthy pagans such as Plato--and infants. These necessarily ignorant, and thereby unworthy of heaven, are said by some to spend their afterlives (assuming the infants die before baptism) in Limbo. Limbo is a kind of place which isn't heaven, but isn't hell either. There, it is to be presumed, Plato, Aristotle and other pagan greats debate and think great thoughts while changing diapers and otherwise tending babies.

Another meaning for "invincible ignorance" is the condition resulting from a refusal to accept evidence or argument. This is referred to as a logical fallacy, sometimes. It is the ignorance I address in this post, and was also I believe referred to by the man quoted above, a French physician and philosopher of the Enlightenment.

It is the refusal that characterizes ignorance of this kind. You or I may be ignorant simply because we don't know something or other for perfectly acceptable reasons--acceptable in the sense that there is no deliberate effort not to know something or other. Invincible ignorance is ignorance by choice. The invincibly ignorant choose not to know. Their ignorance is the result of their willing rejection of knowledge or the effort to know.

According to Julien Offray De La Mettrie, our happiness depends on this kind of ignorance. Judging from the nature of the quote, he probably had ignorance of some thing or things in particular in mind. But ignorance of anything which disturbs us can contribute to our happiness. Ignorance is bliss in some circumstances if not all circumstances.

But the refusal to consider an assertion or an argument, or the evidence which supports them, is different from a refusal to know something in the sense of experiencing something. You can have perfectly good reason, I would think, to refuse to know what it's like to murder someone or torture someone and can hardly be blamed for balking at having knowledge of what it's like to do so. In some cases, then, the desire to be invincibly ignorant is quite understandable. Some knowledge isn't good.

Sometimes an argument or assertion is so absurd there's no point in giving it any serious consideration. Judgment must be exercised in determining absurdity, though. Judgment is something we come to lack more and more these days, at least here in God's favorite country.

It strikes me we live in a time when people are less inclined than ever to consider any position that may challenge or undercut personal, political, religious or cultural views. It may be that such consideration is too trying; the world is more complicated than it has been in the past, in great part because there are more of us needing and demanding limited resources. It may be that the uncertainty of these times causes us to cling more than before to cherished and comfortable thoughts and customs, particularly where religion and politics are concerned, and to so dread what is different as to disregard it as much as possible rather than try to understand it.

But I'm concerned that fear and uncertainty and the desire for the happiness that results from ignorance aren't the only motivations behind invincible ignorance. I'm concerned that many of us are invincibly ignorant simply because we have accepted the view that many intellectuals and academics have propounded for some time. What I'm thinking of is what has been associated with the word "postmodernism" rightly or wrongly. That is, an adverse reaction to the Enlightenment and the faith in science which dominated modern Western culture for two or three centuries, until the 20th century.

A skepticism regarding the extent to which science can cure all our ills and make the world a paradise is understandable. But that skepticism has been associated with a distrust of reason and logic generally; with the view that they are mere constructs of a social and political tradition or culture, no more admirable or desirable, or worthy of respect, than any other construct.

If that's the case (not "true", of course), why is there any point in being anything but invincibly ignorant? We can ignore, refuse to consider, anything we like. There's no basis on which it can be said that assertions or arguments different from those we favor are to be preferred. There's no reason to consider the evidence in their support. There's no reason to think, in fact, or second-guess ourselves, when what others think or claim is no more worthy of respect or acceptance to what we believe and like already.

The invincibly ignorant are fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth.

Wednesday, September 12, 2018

Happy Birthday, H.L. Mencken. Wish You Were Here.

The Sage of Baltimore was not a religious man and did not believe in an afterlife. If there is one, though, his rightful place in it would not be in heaven, of course, nor even in purgatory, but instead in the First Circle of Hell according to Dante along with other great pagans. If it's possible to return from the afterlife and, if nothing else, haunt this sorry world, I think he would be with us now, if only to enjoy the increasingly perverse course of our Great Republic and congratulate himself for having anticipated so well the decadence of our democracy.

I think Mencken had his faults, and have described them previously in this blog. But I know of nobody in the history of American journalism or opinion who wrote so well, and so savagely, of American politics and politicians, and American culture (I can almost hear him say "such as it is") with the exception of Gore Vidal. I regret that he can't write of the current occupant of the White House and the rogue's gallery of our national leaders. How well he would excoriate them, revile them!

We have people enough in journalism and elsewhere who do or would do the same, of course, but either the times or the people have changed. Criticism as we now know it is crude and often vulgar, if omnipresent thanks to the Internet and social media. Now people of all kinds, regardless of levels of intelligence, wit, literacy or sophistication, can express their opinions regarding current events and figures of significance and popularity, and do so with some relish. Unfortunately, they for the most part are incapable of doing that well. Just read what passes for commentary these days, or worse yet the comments readers can now make regarding the commentary.

And yet I think that those who are today professional commentators and pundits, who express their opinions weekly or daily on television, newspapers and journals are, in an odd way, actually more restrained than Mencken was in his heyday. Read what Mencken wrote of such worthies as Woodrow Wilson and William Jennings Bryan, for example. There's nothing like it being written now.

Perhaps "limited" is a better word than "restrained" though. Limited, that is, in ability, knowledge and intelligence. Someone with great powers of expression, like Mencken, can mock and revile far more effectively than someone who is merely consumed with hatred and self-righteousness as so many are today. Today's political figures, and especially our current president, are barely capable of expressing themselves, verbally or in writing. Against Mencken they would appear embarrassingly overmatched.

And I think it would do our nation a great deal of good if they were overmatched, overtasked and overwhelmed by a great writer and critic. They would be shown to be the mediocrities which, at best, they are, and the strikingly small and pitiable people they are and which, perhaps, we've become.

If you can return, Mencken, please do. And hurry.

Friday, August 24, 2018

The Enduring Appeal of Freaks and Freak Shows

Freak shows were characteristic of carnivals. I don't know if they still exist, but if they don't in the form they have in the past it seems we can't do without them as we've managed to replace them with something similar. They must satisfy some need we have. It delights us in some strange sense to see people who are deformed even if they're repulsive. My guess is it does so because it makes us feel we're better or at least normal when compared with those who clearly are not, provided they're displayed in a manner which poses no threat. They provide us with a kind of reassurance. Through them we think ourselves acceptable, and demonstrably so.

There are those of us who still enjoy the deformity and disability of others, I'm sure, but we're not as willing to express our enjoyment as openly as we did and could when invited to view freaks of nature as they were called by paying a fee and visiting them as they posed in tableau at some local fair. Much as we are inclined to inflict pain on others, there's been a decline in the tendency to do that publicly, although our recent toleration and approval of hate and the hateful on the national stage makes one wonder whether that decline will continue. One doesn't want to be accused of "political correctness" after all.

I think freak shows have been replaced, by reality shows. I suspect others think so as well. The similarity is fairly clear.

Some reality shows unashamedly center on people who are physically uncommon, e.g. they are morbidly obese. Some center on people who have problems of a particularly disturbing nature, which impact others visually, e.g., hoarders. Their lives are displayed in detail. Generally, such shows also are carefully structured to have, in most cases, a "happy ending" where there is some kind of redemption or at least the hope of redemption. The physically unusual is somehow rectified, a house full of rubbish is cleaned. Nonetheless, peculiarities, physical or psychological, are on display for our entertainment though we watch them from some comfortable, private venue and not at a public showing.

Some modern day "freak shows" are more subtle, however--if that word can be used when exhibitionists are observed by voyeurs. They involve anything from people beating one another senseless with fists and feet, to people brought together in an unusual environment and manipulated in certain respects so that the manner in which they react is displayed, to men or women being romantically paired with a number of women or men and made to choose one or another of them for marriage while we watch. In the case of such shows, what is put on view for the public at large are not physical deformities or psychological or mental deficiencies in particular. Instead, individuals are treated as freaks once were; they are made the objects of our attention, our review. We watch them and marvel at them or use them by comparing them, usually unfavorably, with ourselves. They become freaks, eventually, if that suits the producers or directors of the shows.

Freaks shows and reality shows appeal to the voyeur in us. A voyeur is not necessary someone who derives sexual pleasure from watching others, but may also be someone who enjoys the pain or distress of others and wishes to observe it, or to observe people in sordid or scandalous circumstances. They appeal, in other words, to what is base in us and we debase ourselves by watching them. Their appeal and popularity doesn't speak well for us or our hopes for improvement.

Friday, August 10, 2018

To Hell in a Handbasket

But although we're being told that the America we love is disappearing due to massive demographic changes, fear and loathing (trembling too, no doubt) are not reserved for immigrants and foreigners only. Paroxysms of anger and dismay may be triggered by so many things in these fraught times. We perceive ourselves to be besieged by enemies of all sorts. There is, of course, the media which our tiresome and unusual president tells us repeatedly is "the enemy." Then there are efforts to prohibit speech of particular kinds on college campuses. There are fascists and white nationalists everywhere. Nuns are being forced to purchase contraceptives, according to our Attorney General. Chicago is a war zone. NFL players kneel or sit down or raise fists when the National Anthem is played.

One must wonder if other nations are similarly plagued by outrage and anxiety and whether expressions of outrage and anxiety occur on a daily basis in other, less favored, lands. Here, we wake up to revelations of monstrous conduct each day, or in the rare case when there is none, we're regaled with new information regarding those evils which have taken place.

It's as if we've been consigned, as a nation, to the Fifth Circle of Hell as described in Dante's lighthearted Inferno. There, those who have committed the sin of Wrath are either engaged in constant conflict with their fellow sinners, or lie sullen and silent beneath the waters of a river, stewing, as it were, wrathfully. We are a nation of the irate.

I wonder how this came about. I don't think we always were so highly annoyed at most of what takes place, though certainly some of us always have been. We have all come to consider ourselves dispossessed in one manner or another, but unfortunately there are those who have not actually been deprived of anything but what they think is their due or is proper rather than anything tangible, and they are the loudest in their discontent. I refer to those who are offended by other people doing things or saying things which, it's believed, shouldn't be done or said. What's done or said in many cases does no harm to those who object to it--some monuments are taken down, some pundit or institution is boycotted, some people speak a language which isn't English, etc., or someone is a boor.

What has brought us to this? Our ancestors faced economic depression and terrible wars. We face nothing like that. Instead, we take with great seriousness what people say and ignore our many problems. The self-righteousness required to feel anger and outrage over such things is monumental.

This kind of pettiness is troubling. If we react in outrage to such things, who knows what we'll do if we're actually subjected to some real injustice, or are impoverished for some reason, or grow suddenly and seriously ill. Perhaps we'll lose all control, all reason. Has there ever been a case where a nation has fallen apart because it's people are, for the most part, spiteful and small-minded? It would make us unique in history, I think.

If you've ever wondered about the phrase "going to hell in a handbasket" and have done an Internet search of it, you'll probably find as I did that it is an American colloquial expression the origin of which is uncertain. Why is going to hell in a handbasket different from going to hell in some other manner? What makes it remarkable or poignant or interesting enough to comment on; what distinguishes it? If you search for the definition of "handbasket" you'll find such useful definitions as "a small basket, which may be carried by hand."

The articles which may be carried in a handbasket are small, relatively speaking, and that may be why the saying seems especially apt at this time. We've become small as have our concerns and grievances and so will fit in a handbasket as we're carried by some force or by ourselves to a hell of our own creation.

Wednesday, August 1, 2018

Charged with Grandeur

The 19th century English poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, had a remarkable way of using language in his poetry which sets him apart from other poets of the Victorian era, and from the English Romantics generally. It's hard to describe, for me at least. Hopkins' poems seem playful sometimes, sometimes erudite, sometimes philosophical. Often philosophical, I think, and even more often religious.

The language he employs can be archaic, antiquated. He was fond of alliteration. He seems to have sought to use unusual words--unusual groupings of words--in his poetry, and I believe this sometimes saves him from the sanctimony which too often infuses the writings of the religious, and from being sentimental. Sanctimony and self-righteousness was prevalent among the Victorians. Sentiment was prevalent among the Romantics. In a way, his poetry seems almost modern.

"The world is charged with the grandeur of God." This is the first line of his poem titled, unsurprisingly, God's Grandeur. It's an arresting opening line. "Charged" suggests electricity, a force invisible but pervasive, empowering the world as it courses through all that it is, all that's in it. "Grandeur" as in splendor, greatness, majesty, magnificence. The world seethes with God's splendor; it's an embodiment of it. It shines forth "like shook foil."

It seems a Stoic view, to me at least. Perhaps a view of the world even older than that of the Stoics. This can be inferred from another of his poems, one with a lengthy and somewhat awkward title, That Nature is a Heraclitean Fire and of the Comfort of the Resurrection.

Heraclitus was one of the pre-Socratic philosophers, and what we know of what he thought and taught is fragmentary. Some of what he is said to have said is well known, like the statement that one never steps in the same river twice, and all is flux. The fragments we have sometimes seem contradictory, and he is criticized for this by Plato and Aristotle. The Stoics valued him, however, and it seems Cleanthes especially admired him. The Stoics seemed to have admired his cosmology, particularly his view of the universe as being eternal and its basis being a kind of fire, divine it would seem as the Stoics conceived of it. God to him and to the Stoics was immanent in the world.

It seems Hopkins thought well of him also, given the title of this poem. Like God's Grandeur the poem begins with an artful, witty, even musical-sounding celebration of the world. "Nature's bonfire" is referred to. That's the only clear reference to anything like the fire of Heraclitus I can see in it.

In God's Grandeur, the celebration of Nature is followed by lines which express regret that the world has been sullied by man and his toils, bleared and smeared by it, in fact. Then, hope and wonder is expressed that there remains something beautiful and divine in nature, nurtured still by God in his capacity as the Holy Ghost, or as that person of the triune God called the Holy Ghost.

In Nature is a Heraclitean Fire the celebration ends in sad reflection on the temporary nature of man: "Man, how fast his firedint, | his mark on mind, is gone!" But these broodings are ended by the knowledge of the Resurrection to come after death: "In a flash, at a trumpet crash, I am all at once what Christ is, | since he was what I am, and This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, | patch, matchwood, immortal diamond, Is immortal diamond."

That's very impressive stuff, to me. And perhaps it expresses and explains better than anything I've read the appeal of Christianity at its beginning to those who came to be called pagans, and its success even though the wisdom of pagan philosophy was acknowledged and admired. It was an appeal the mystery cults may have had as well to an extent, but were the gods they extolled "what I am" as Jesus was, before his Resurrection, fully man? But also fully God, it seems, inexplicably to me but perhaps this was, and is, of little concern to true believers, and pagan philosophy forgotten in the acceptance of mystery.

Monday, July 23, 2018

Great Pan Is Not Dead

According to Plutarch "Great Pan is Dead!" are the words uttered in a loud voice (sometimes called a "divine voice") heard by the sailor Thamus on his way--by boat one would assume--to Italy while travelling there during the reign of the Emperor Tiberius. The extremely fat and inordinately glib Christian apologist G.K. Chesterton, who could be a witty fellow though over-fond of quips, thought Pan to be the only pagan god said to have died, and thought his death somehow connected with the death, or perhaps the birth, of Jesus.

I'm not sure if it mattered all that much for Chesterton's purposes, but I suspect the birth of Jesus somehow precipitated the death of Pan. I think a case can be made that it did, though it took quite some time to do Pan in. This had something to do with the birth of theology, according to Chesterton.

Others, such as Robert Graves, thought the story the result of some confusion, and believed the great shout had been mistranslated over time or mistold. He believed there was no Thamus, but there was a Tammuz, another pagan god who died and whose death was remembered through a ritual which was being performed and was overheard by...someone.

It does seem jolly old Chesterton was mistaken about pagan gods and their birth or death, for various of them did die or their consorts did, and it was their death and resurrection which became the subject of the mystery religions such as that of Mithras, and Isis, and the Great Mother.

Pan was the god of nature, of wild nature that is; but also of shepherds and flocks, and music through the rustic flute. He's often confused with satyrs, due to the fact that he had the horns, hoofs and hindquarters of a goat. And it must be said he was inclined to physical pleasures as well, which of course rendered him abhorrent to many Christians. As a nature god he wasn't worshipped in temples but in caves or wooded groves. He was born in Arcadia. His Roman counterpart was Faunus.

But if he died so long ago, he seems to keep coming back, Chesterton and, perhaps, Jesus notwithstanding. He came back during the Renaissance, as did so much else pagan in spirit. He was a favorite of the 19th century Romantics, and is even now worshipped by neo-pagans. He is part of the great inheritance of Western culture that is pagan antiquity, and like it will not die much as some wish it would, who are blithely ignorant of the debt owed to it even, and perhaps especially, by Christianity.

I know little of Wiccan or neo-paganism generally. I'm not inclined to engage in rituals or ceremonies which are meant to revive or mimic ancient religious worship. Nor am I inclined to worship any of the old gods. But I am pleased that there seems to be a revival in respect for and reverence towards nature--by which I mean the physical world, the universe. We've believed ourselves to be nature's master for far too long, and are paying the price of the monstrous credo we've accepted here in the West; that we like the God of the Abrahamic religions are apart from nature rather than a part of it. We will pay more for our self-regard.

Stoicism also keeps coming back, as the modern resurgence of that philosophy makes clear. But it's always been around in one sense or another, and it's injunction to "live according to nature" is one that will be accepted it's to be hoped. It may have to be accepted if we're to survive.

But if I were to worship any of the old gods, I think Pan would be one of them, along with Apollo and Hermes, the one the god of reason, the other the bright intelligence of the universe. And Pan the god of the physical nature of all living things.

Sunday, July 15, 2018

Our Willy

Vain, verbose, muddle-headed, ignorant, boorish, morose, opinionated, excitable, scatter-brained, loud-mouthed, meddlesome...all adjectives used at one time or another to describe Kaiser Wilhelm II, the "Kaiser Bill" of fame of the Great War, or World War I as we came to call it after an even greater war (in terms of its extent and destructiveness) came along.

I was asked recently what Roman Emperor the current president of our Glorious Republic most resembled. I found this required a certain amount of thought. None of the great monsters who ruled Rome seemed appropriate; Caligula, Nero for example. One of the most ridiculous of emperors came to mind--Elagablus, I mean--almost immediately, but his oddities were different than those of the present occupant of the White House. The Empire had many bad emperors, bad for various reasons, but I was hard pressed to think of one who is a match.

The fact is, we have a more recent figure in history who matches this president quite well. Wilhelm, or "Willy" as his many relatives in similar positions of power throughout Europe would call him, was most of all a nuisance. But as a ruler of a nation, an autocrat, his influence was vast. He was a nuisance in internal affairs, a nuisance in foreign affairs. His ministers did his best to limit his influence, to control his sudden and sometimes inexplicable intrusions into careful plans and negotiations, but to no avail. He somehow managed to insert himself in a matter and send it spinning into chaos. He insulted, he repulsed, he badgered. A colossal and offensive know-it-all, he offended fellow heads of state with words of advice.

His state visits to other nations were stressful to those involved. Nobody knew quite what he would do or say. He was made an honorary admiral of the British Royal Navy and apparently took this kindness so seriously he thought it appropriate to express his opinion regarding its operations to those who were actual members of that branch of the British military. He hounded the poor Tsar unmercifully, always telling him what to do. He exasperated his grandmother, Queen Victoria. His cousin Edward, who became King of England, thought him malicious.

It seems that as war approached he wanted peace. He managed, though, to assure war came by his fecklessness and his remarkable ability to take inconsistent positions and stances, generally motivated by whoever it was he happened to speak with last. Once at war, as might be expected, he was eager for victory, and so became the bane of his generals' existence. A paranoid, he felt that he and Germany were constantly under appreciated and threatened by all other nations, with the possible exception of Austria, which he merely looked down on.

It appears he actually had some good traits. He may have lived well enough as an eccentric country gentlemen in other circumstances, as it seems he did after he abdicated at the war's end. But he was a loose cannon as leader of a powerful nation in a war far too full of cannon of other kinds.

Which brings us, however unwillingly, to the present. The similarities between these two peculiar men seem evident to me. But the times are certainly different. And while Willy's advisers did what they could to control and discourage him from capering too wildly about the world stage, our president's advisers, such as they are, seem incapable of controlling him nor do they seem to want to discourage him. Neither do most members of the Republican Party who seem content to be complicit with him in many matters. Except, of course, where the money with which they retain their positions is concerned, and it may be that his antics with tariffs and economic policy may finally bring the various shills who make up the Congress to do what's required to stifle him.

It's a very odd thing, that such a man should be where he is, and it makes one concerned regarding the fate of God's favorite country. One prefers one's villains to be intelligent, cultivated, knowledgeable if immoral and unworthy. The devil is a gentleman, so it's said. A small, mean, petty, ignorant and venal man makes a most annoying bad guy. Even an embarrassing one.

Sunday, July 1, 2018

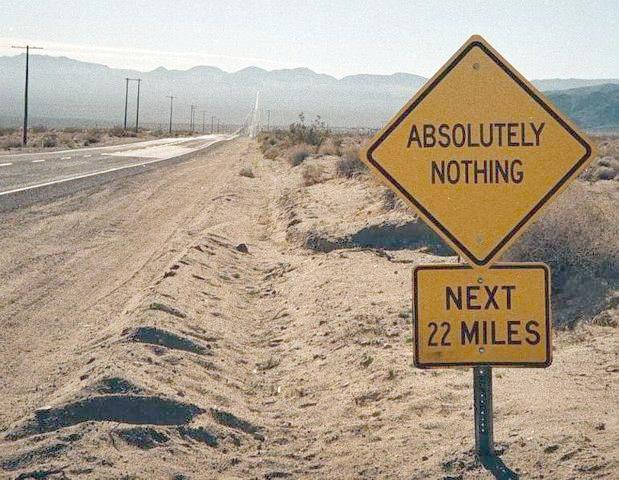

Meet the Nothing

There's something called "the Nothing." There's something called "Nothingness." They are (are not, perhaps) a concern to certain philosophers of a certain kind. Apropos of nothing, Cicero once said (I paraphrase) that there is nothing so absurd that some philosopher has not already said it.

"Nothingness" I suppose represents the state of being nothing, or perhaps is characteristic of nothing, or is the quality of nothing or is characteristic of "the nothing." Nothing is, apparently, the opposite of Being, or its negation. I may be mistaken though. I know nothing of the Nothing.

Heidegger the Great and Powerful wrote of the Nothing in his inaugural address on becoming rector at Freiberg, where he infamously made some speeches praising and indeed glorifying Hitler as, among other things "the future of Germany and its law." I spent some time asking questions about this speech in a philosophy forum I frequent, and eventually was duly accused of bad faith for doing so and, I would think, also because I didn't understand what he was saying. Which was nothing? I still don't know.

I think Heidegger is something of a sacred cow in some philosophical circles and his followers eagerly leap to his defense whenever he is questioned or mocked. They may be all the more avid in his defense because there's no doubting the fact that he was a member of the Nazi party, and never publicly expressed any remorse over that membership, nor to my knowledge did he ever publicly express criticism of the Nazi regime before, while or after it was in power. As a result, those who defend him are defensive in doing so.

But I've been told many times, sometimes sternly, that his misdeeds in life have nothing to do with the merits of his philosophical works, and I would say that it's likely his fondness for Hitler and the Nazis at the least did not arise due to his writings regarding "the Nothing." Had, in other words, nothing to do with the Nothing.

I think Rudolf Carnap said all there is to say about "the Nothing" as it is referred to in the inaugural address. What he says essentially is that "nothing" shouldn't be spoken of as if it is something or used as if it is a name for something, and if it is so used it leads to meaningless propositions. But Heidegger seems to understand this and indeed says he does in the address. Nevertheless, he says this is a defect in logic, not in use of the word "nothing" or indeed in "the Nothing." "The Nothing" is encountered only when one is "suspended in dread" (or anxiety). It's only this encounter which allows us to understand Being. "Being" apparently refers to that which is. That or those which is or are have "Being."

"Being" and "nothing" are concepts, names, or something which fascinate many philosophers, I'm sorry to say. "Being" seems to me to suffer from some of the same problems as "nothing" or "the Nothing." It may be used as a noun or name, and is treated as if it is something, a quality possessed by that which is, as opposed, apparently, to "that "which is not. But at least unlike "nothing" or "the nothing" it actually refers to something which exists; indeed, everything that exists. "Nothing" doesn't refer to any thing.

The fascination with "nothing" seems to be related to a question which in turn is a fascination of some philosophers. That question is: "Why is there something instead of nothing?"

Now some, like me, would say that there are problems with that question. That problem as I see it is that it also is premised on an assumption that there is something that would exist if something didn't exist, called "nothing." One can ask if one wants to "Why there is something?" but one can't then refer to anything that is "instead of" something. Nothing would exist, true, but "nothing" doesn't replace something.

I think the question when posed as, "Why is there something instead of nothing?" or "Why is there something?" isn't one that can be answered by philosophers. If it can be answered at all, it would be an explanation of the fact that things exist, and that explanation would seem to be one that would formulated by science, not philosophy. That is, unless one is satisfied by an answer which is merely speculative.

It is a question which invites not merely speculation but the use of words in the fashion used by Heidegger and others when it comes to "nothing" and so invites confusion and what Carnap calls "pseudo-statements."

Carnap suggests such statements by philosophers may serve to do what poetry and art does, or music. For me, that means that such statements may be evocative, and evoke a kind of knowledge or appreciation of the true or correct. That may be generally true, but as I think Carnap observes the poets, artists and musicians or composers do a better job in this respect that do philosophers. Some of the most profound feelings I've experienced arose from reading poetry or listening to music. But "the Nothing" inspires nothing in me, I'm afraid. Don't tell anyone, though. This is between you, dear reader, and me.

"Nothingness" I suppose represents the state of being nothing, or perhaps is characteristic of nothing, or is the quality of nothing or is characteristic of "the nothing." Nothing is, apparently, the opposite of Being, or its negation. I may be mistaken though. I know nothing of the Nothing.

Heidegger the Great and Powerful wrote of the Nothing in his inaugural address on becoming rector at Freiberg, where he infamously made some speeches praising and indeed glorifying Hitler as, among other things "the future of Germany and its law." I spent some time asking questions about this speech in a philosophy forum I frequent, and eventually was duly accused of bad faith for doing so and, I would think, also because I didn't understand what he was saying. Which was nothing? I still don't know.

I think Heidegger is something of a sacred cow in some philosophical circles and his followers eagerly leap to his defense whenever he is questioned or mocked. They may be all the more avid in his defense because there's no doubting the fact that he was a member of the Nazi party, and never publicly expressed any remorse over that membership, nor to my knowledge did he ever publicly express criticism of the Nazi regime before, while or after it was in power. As a result, those who defend him are defensive in doing so.

But I've been told many times, sometimes sternly, that his misdeeds in life have nothing to do with the merits of his philosophical works, and I would say that it's likely his fondness for Hitler and the Nazis at the least did not arise due to his writings regarding "the Nothing." Had, in other words, nothing to do with the Nothing.

I think Rudolf Carnap said all there is to say about "the Nothing" as it is referred to in the inaugural address. What he says essentially is that "nothing" shouldn't be spoken of as if it is something or used as if it is a name for something, and if it is so used it leads to meaningless propositions. But Heidegger seems to understand this and indeed says he does in the address. Nevertheless, he says this is a defect in logic, not in use of the word "nothing" or indeed in "the Nothing." "The Nothing" is encountered only when one is "suspended in dread" (or anxiety). It's only this encounter which allows us to understand Being. "Being" apparently refers to that which is. That or those which is or are have "Being."

"Being" and "nothing" are concepts, names, or something which fascinate many philosophers, I'm sorry to say. "Being" seems to me to suffer from some of the same problems as "nothing" or "the Nothing." It may be used as a noun or name, and is treated as if it is something, a quality possessed by that which is, as opposed, apparently, to "that "which is not. But at least unlike "nothing" or "the nothing" it actually refers to something which exists; indeed, everything that exists. "Nothing" doesn't refer to any thing.

The fascination with "nothing" seems to be related to a question which in turn is a fascination of some philosophers. That question is: "Why is there something instead of nothing?"

Now some, like me, would say that there are problems with that question. That problem as I see it is that it also is premised on an assumption that there is something that would exist if something didn't exist, called "nothing." One can ask if one wants to "Why there is something?" but one can't then refer to anything that is "instead of" something. Nothing would exist, true, but "nothing" doesn't replace something.

I think the question when posed as, "Why is there something instead of nothing?" or "Why is there something?" isn't one that can be answered by philosophers. If it can be answered at all, it would be an explanation of the fact that things exist, and that explanation would seem to be one that would formulated by science, not philosophy. That is, unless one is satisfied by an answer which is merely speculative.

It is a question which invites not merely speculation but the use of words in the fashion used by Heidegger and others when it comes to "nothing" and so invites confusion and what Carnap calls "pseudo-statements."

Carnap suggests such statements by philosophers may serve to do what poetry and art does, or music. For me, that means that such statements may be evocative, and evoke a kind of knowledge or appreciation of the true or correct. That may be generally true, but as I think Carnap observes the poets, artists and musicians or composers do a better job in this respect that do philosophers. Some of the most profound feelings I've experienced arose from reading poetry or listening to music. But "the Nothing" inspires nothing in me, I'm afraid. Don't tell anyone, though. This is between you, dear reader, and me.

Monday, June 18, 2018

Of Human Cruelty

The image above is, of course, taken from The Twilight Zone of happy memory. It occurs to me that American television hasn't done any better than this series, especially when it tries to imitate it. The concept has been used since then often enough, but it's too familiar now to have any real effect.

Nonetheless, there's reason enough to believe that we earth creatures should be locked away for our own safety and that of others inhabiting this planet, and in fact for the safety of the planet itself. We're a singularly destructive species and are far more destructive than any other animal. Some of us are locked away, of course. We do that to our own kind. We do a great deal to our own kind. Being so minded, we don't hesitate to inflict pain and confinement on the other miserable occupants of this world.

What distinguishes us from the other animals which kill, maim and destroy here is not merely our greater ability to do so, however. It's the fact that unlike them, when we do harm we're not driven by instinct or hunger or the effort to survive in most cases. We want to inflict harm and intentionally destroy others; we take pleasure in it or are indifferent to it. We are, in a word, cruel.

Although Stoics have popularly been thought callous and indifferent, it should be clear that a true Stoic can't be cruel. In order to be cruel, a person must be disturbed by or desire things outside/his her control. In fact, just about every negative feeling or action has its basis in our attachment to such things. We hate others for what they are or do or think or say, although they are not within our control. We desire or fear things not in out control, and therefore steal or seek to possess them as most efficiently we can or avoid or destroy them. We require that others do what we want them to do, despite the fact they're not in our control. None of this would take place if we sought only to do the best we can with what is in our control.

We can concern ourselves unduly with things outside our control without being cruel, however. Cruelty requires something more of us. Not only do we want to control what isn't in our control, we want to do so in a way which we know will inflict unnecessary harm or pain because it pleases us or because we don't care that unnecessary harm and pain will occur as a result of our action. The cruel person isn't just misguided. The cruel person is evil.

Cruelty has always been a human trait, but there are times when we are, in general, more cruel than in others. The Nazis are thought to have been impressively cruel, for example. Were they cruel merely because they were evil? It may be they were convinced they were part of a master race and that the elimination of undesirables was for the greater good, or that certain peoples were inherently evil. Sometimes, the religious have acted cruelly. People of other religions or having no religion were burned and tortured for that reason by those who thought it necessary or appropriate. Does this mean they were evil? Or is it better to say they did evil things? Are people cruel if they believe the suffering of others is necessary in some peculiar sense?

Such fanaticism may be a cause of indifference to suffering imposed, but it doesn't follow that the suffering is pleasurable to those who impose it. What would seem needed in addition for a person to be cruel is the knowledge that the suffering they cause others is not necessary. The cruel person causes suffering for no reason but his/her own pleasure, or merely for the sake of causing others to suffer.

Is the apparent policy of the current government of our Glorious Republic to separate parents seeking to enter God's favorite county illegally from their children cruel? It plainly isn't necessary to prevent them from doing so; there are other means to do that--the Great Wall of the U.S. has yet to be built, but it is presumably an option. The separation obviously causes suffering. The law already provides penalties. This therefore is something more than imposing the penalties set out in the law for an illegal act. This is a punishment we've decided to impose in addition to those penalties.

These are questions which should be asked, issues which should be considered, by an honorable people.

Thursday, June 7, 2018

I Pardon Myself--Ego Absolvo

There's something laughable about the idea of someone pardoning himself/herself, or perhaps a better word would be "incredible." It makes no sense; or no common sense, in any case. If I've done wrong, I generally have done wrong to someone other than myself. If anyone has any business pardoning me in that case, it would be the person I've wronged. It would be strikingly unjust if I could pardon myself. It would be evidently unfair.

The pardon power isn't an exclusively American creation by any means. Kings and Queens had that power for centuries. It was apparently accepted that they had the authority to grant clemency or even wipe from the record of the law any crime committed by a subject. I wonder if this power derived in some sense from the belief in the King's Touch. It was thought that a king could cure someone of the skin disease called scrofula by laying his hands on the stricken. Henry VIII, who certainly had the power to detach the heads of subjects if not by his own hands then by others, is shown using them (his hands, I mean, not the detached heads) to banish scrofula from some fortunate man above. The King's Touch itself probably derived from the power of Jesus and the apostles, and even some saints, to heal by laying their hands on the stricken.

Catholic priests, of course, have--or at least had (it's been some time)--the power to absolve, pardon that is to say, some sins by virtue of the Sacrament of Penance or Confession. They possessed the power because they were in effect the authorized representatives of Christ. The Catholic Church believes itself to be in direct succession the heir of the apostles. It is the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, after all. Thus, its agents may forgive certain sins as it's thought the apostles did.

A King, Queen and I suppose some would say a president is in some sense treated, at least, as sacrosanct. There's something about their person while they hold their office that renders them untouchable, incapable of interference. There's a hint of mysticism in this. Our current president's lawyers have opined that a president as the chief officer and representative of the law of the land cannot obstruct the law, as the president is, in a way, the law as much as a person can be. The president thus becomes the law incarnate. The president cannot obstruct himself, right?

In any case, I think it's fair to say that for quite some time, and perhaps ever since we've had Kings and Queens or their equivalent, or priests or their equivalents, it's been accepted that certain persons, because of their special status or capacity, have the authority--the power--to pardon or absolve others of their crimes or sins, and even to cure them of certain diseases. But I don't think it's been accepted that certain persons have the authority to pardon or absolve themselves. Ego te absolvo was the formula used by priests, in nomine patri, fili et spiritus sancti. "I absolve you in the name of the father, the son and the holy spirit." Never, as far as I know, has anyone ever said "ego absolvo", i.e. "I absolve myself."

Our current president may be the first (and one can hope last) troll president, in the sense of an Internet troll. He seems to delight in antagonizing, offending, disrupting discourse, specific people or groups of people through the use of inflammatory, disturbing and even ridiculous statements. So there are those who think he's made the claim he can pardon himself merely to provoke. I hope that's the case and that he's merely intent on being annoying, as is his wont, or merely engaged in the kind of tactical display the more brutish of those in power sometimes practice. But he may in fact mean it.

While the president is in office, he/she is immune from prosecution. That seems to have been determined by the bulk of legal authorities; that the president is merely subject to impeachment if the designated crimes are committed while in office. Once out of office, the president is subject to prosecution, however. So, the concern would be that a president would pardon himself of crimes committed by him/her while in office. In that case those crimes, having been pardoned, could not be the basis for prosecution even after the president leaves office. The courts haven't weighed in on the idea of self-pardoning. Perhaps they'll have a chance to do so soon.

Sunday, June 3, 2018

Tom Wolfe: An Appreciation

I was always a fan of what was called the "New Journalism" as practiced by Tom Wolfe and a few others. I particularly liked his Radical Chic which so devastatingly mocked the propensity of rich, intellectually-inclined white who hosted events for such as the Black Panthers, and mocked Leonard Bernstein in particular,. "New Journalists" as I understood them included Norman Mailer, whose Armies of the Night and Miami and the Siege of Chicago were personal favorites. Then of course there was Hunter S. Thompson, though he I think was referred to as Gonzo Journalist, perhaps because his new journalism was associated with the intake of drugs.

It's odd, then, that Mailer was among those who criticized Wolfe for not really being an artist or novelist, despite the fact or perhaps because he wrote so well. John Updike was a critic as well. I've never had enough interest in Updike to read any of his work. Mailer interested me, though I thought his writing would become grotesque now and then, particularly when the subject being addressed was sex.

Wolfe's journalism was very good indeed. The Painted Word and From Bauhaus to Our House are impressive. But I find it hard to understand why his novels failed to pass muster with some; why they're considered somewhat lacking by other novelists. I suspect, though, that this is the case merely because they tell interesting stories and tell them well, and also sell well.

Wolfe's novels are picaresque, in the sense I think that the Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter and The Golden Ass of Apuleius are as well. They're adventures involving protagonists who are recognizable who encounter ordinary and extraordinary circumstances and react to them in ordinary and extraordinary ways. Most of all, they're enjoyable.

It may be that art has come to mean that which cannot be enjoyed, that which is not entertaining. Art is supposed to inspire in us some feeling which isn't associated with pleasure, being too profound. It can be disturbing, grim. It must cause us to think--never a pleasant experience for most of us. It may move us to tears or anger. It is supposed to evoke some strong emotion.

That may be so, but if so is dispiriting, I think, for the artist and those who patronize the artist or his/her work. What we experience in life can be dreary enough. Why seek to create dreariness, or seek out such creations, when we're exposed to it in "real life" and allow it to disturb us from moment to moment?

In dark times, entertainments are few and become coarse. Those who can tell good stories and tell them well, with wit, imagination and intelligence, should be honored as much as any; perhaps even more.

Sunday, May 13, 2018

A Vulgar Time

"Vulgar" is a word with a very broad meaning. It has Latin origins, and in those origins denotes a mob or common folk. It can mean unsophisticated, crude, offensive, undeveloped, ostentatious, excessive, and ordinary. A most useful adjective..

Thucydides complains that "so little pains do the vulgar take in the investigation of truth, accepting readily the first story that comes to hand." The word "vulgar" as it appears in that complaint has several of the meanings noted, and the complaint itself seems particularly apt to our time.

The picture above is of a part of the Las Vegas strip, and was taken by your charming and delightful old Uncle Ciceronianus during a visit to that ridiculous but amusing place into which have been dumped absurd facsimiles of an Egyptian pyramid, the Eiffel Tower, a Roman arena, a statute of the Emperor Augustus and much more. Personally, I can't think of it as offensive though I'm sure some do. But it's certainly vulgar in various ways and so graces this post. Its vulgarity is of a piece with our time, as excess and ostentation abound among those who've made vast sums of money, from the commonest entertainer to sport stars (also entertainers, when you think of it) and those who manipulate our politics or are politicians, most especially our supremely vulgar president.

As for offensiveness and crudity, they're clearly on display everywhere. Those characteristics are typical of what passes as public debate in our Great Republic. We seem eager to offend when offering an opinion or responding to one, or to a person or event. We even find it offensive to have to do so. We're particularly incensed by anyone who thinks differently than we do or looks different from us, and feel free if not compelled to say so. We resent the very idea that we should not speak our mind in the most offensive manner possible. Thus the current contempt for "political correctness."

Thucydides' complaint is strikingly applicable to our time, I would say. There is no effort to investigate whether something is or is not true, and acceptance of the first thing we hear, or read, is commonplace among us--provided, of course, that it's agreeable to us. How else would it be possible for people to believe what they believe, for people to do what they do, here in God's favorite country?

But our time is vastly different from that of Thucydides in that what comes to hand, for us, is so much, and comes to all of us so easily and constantly due to our technology. We've begun to learn that there are those who take advantage of that technology to provide us with falsities which appeal to us and by which we're manipulated, but being vulgar may take no real notice this is the case in so many instances. We think what we think and why shouldn't we? What right has anyone to tell us otherwise?

Those who are offensive readily take offense, and when offended they're crude in their response. So we revile those we disagree with rather than respond to them. Our response to those we disagree with consist of ad hominems and nothing more.

What comes after vulgarity?

Monday, May 7, 2018

Homage to W. Somerset Maugham

I wonder whether an artist of any kind can be said to long for success. Success is something it would seem great artists would wish to avoid, as their greatness to many is defined--if not measured--at least in part by their lack of success. Great artists are not successful; their work isn't admired during their lifetimes, or sought, and most of all not bought. This appears to be a condition precedent to greatness in an artist.

I refer to artists of all kinds, to painters, writers, composers, musicians. The quality of art is thought to increase with failure in life. Those unfortunate artists who succeed must do so because they appeal to those having money and willing to spend it, i.e. to Philistines. Philistines necessarily are without the ability to discern great art and are instead attracted to the banal, the clichéd, the sentimental and, worse yet, the bourgeois.

So at least is the conceit of many an unsuccessful artist, I would guess, and of those who discover them after they've suffered through life in poverty or enslaved by drugs or as misunderstood genius-deviants-criminals. It's curious that the tortured artist has become something of a cliché. Perhaps the successful artist will come to be lauded and his/her work sought after, and will even be considered great when the artist has passed beyond the allure of genius. There are examples in history. Michelangelo, painter and sculptor, who seems at times to have thought of men and God as being as preposterously muscled as modern superheroes, was a successful artist of his time and is nonetheless considered a great one.

W. Somerset Maugham became extremely successful as a novelist, playwright and writer of short stories. He was a screenwriter too, I suppose. At least, several of his books were made into movies. He was also a success as a public figure, that figure being himself as a well-read, knowledgeable, witty and world-weary literary master, of sorts.

Of sorts, I say. He hasn't been granted iconic status, and has been considered less a writer than the other standouts of the 20th century, such as his contemporaries Hemingway, Faulkner, Joyce, Scott Fitzgerald. Even Anthony Burgess, who apparently admired his work, poked fun at him in his Earthly Powers. Maugham himself pretended (or perhaps even felt) modesty about his work, declaring himself to be in the first rank of second rank writers, or words to that effect. Orwell thought well of him and admired his storytelling and simplicity of style.

So do I. Perhaps he was a good storyteller because he was very well-traveled as well as well-read, listened and observed. He experienced much, and was even for a time with British intelligence, working in Switzerland and Russia after the downfall of the Czar but before the Bolshevik revolution.

He wrote a series of stories about being a spy, naming the protagonist Ashenden. Supposedly, Ian Fleming was inspired by his work to write his James Bond stories.

He has never been considered a great writer. I'm sure there's a reason why that's the case. But I re-read recently his novel The Moon and Sixpence and found myself impressed by the story told if not by the writing. His style of narration is cool, dry and simple, which I find admirable, but the story is a good one as well, although it grows tedious sometimes as he describes the life of an artist apparently based on Gaugin, as related by those who encountered him. What makes the artist remarkable is the fact that he is what would now be called a sociopath or one with a similar personality disorder. He's entirely indifferent to other people, without conscience, interested only in painting. He destroys lives, without any real intent to do so but for merely selfish reasons and is untouched by consequences to others.

Of course, his art isn't appreciated during his life, but he's considered a genius after his death. He destroys his greatest work, apparently content to have done it but not wanting it to be seen by others. I wonder if Maugham was having a bit of fun with the idea of what it means to be a great artist, portraying him as a kind of seductive monster, as inhuman, and telling his reader that he's happy not to be a great artist himself, and the reader should be happy for it as well. Telling his reader that great artists are not admirable, but merely sick. They're not content to be tortured themselves by life, but wish also to torture those they know. Perhaps one doesn't have to be tortured to be a great artist. Instead, one must torture.

I think of Maugham as being similar to Graham Greene. They have the same interest in far away places and in the grotesque aspects of human nature. They both tell a good story. Somehow it's enough, for me. To what extent is it reasonable to expect more? Why be disappointed if an interesting story is told and told well?

Maugham put a symbol on all his books, and that's what is shown above. It's supposed to be of Moorish origin, a charm against the evil eye and talisman of good luck. It brought him luck. I know nothing of the evil eye.

Sunday, April 22, 2018

Regarding Prayer